What is this?

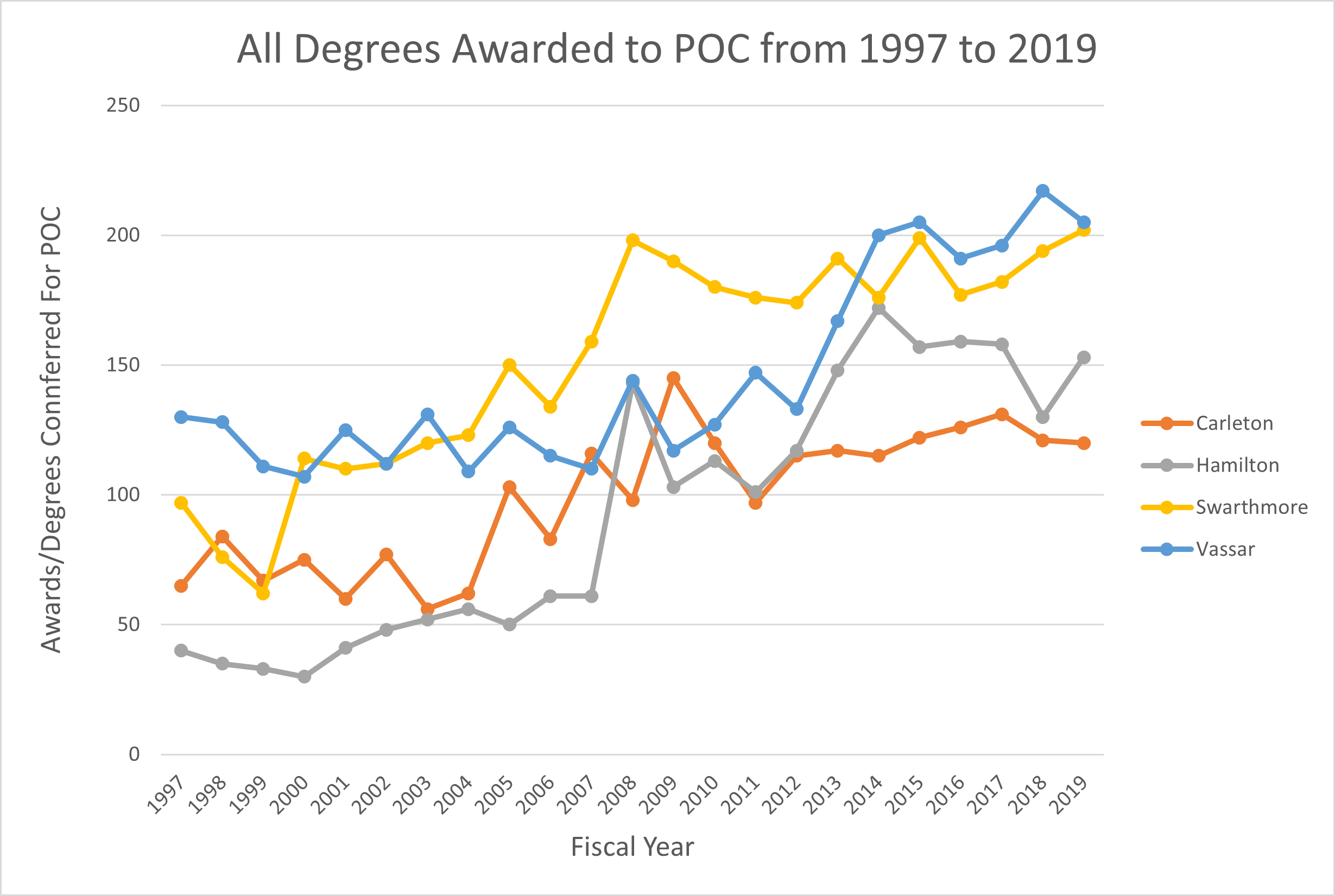

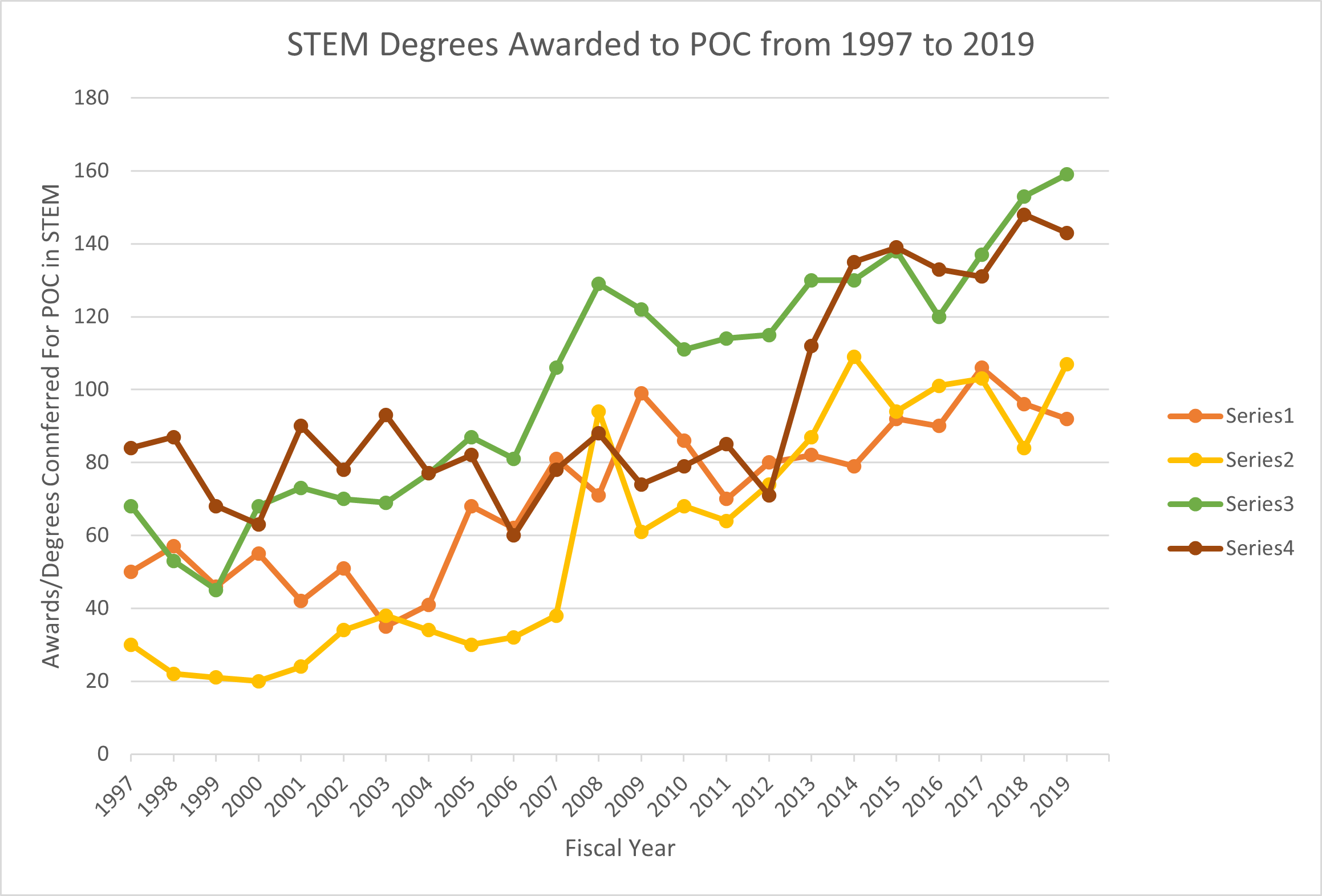

It should come as no surprise that BIPOC students of all stripes are significantly underrepresented in higher education. The root causes of this have been well-studied by other projects, institutions, and organizations, far beyond what we ourselves would be capable of. We are interested, rather, in how the lack of representation affects liberal arts college environments and the students themselves, and where various points in these colleges’ diversification efforts fit within broader national and global moments. The five of us are from four different colleges–Swarthmore, Vassar, Carleton, and Hamilton–and our research and analysis relies primarily on sources from those institutions’ digital archives and other portions of the school websites, alongside data gathered from the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES).

What did we do?

Initially, we focused on the underrepresentation of POC students in academic departments, STEM subjects in particular. However, during our researching process, we realized that, due to how student information is stored and made available by our respective institutions, this question is not easily addressable with the current online archives. Thus we had to change our method, and began researching what we could find related to POC students in general to see how their experience shifted over time. Though this was a reluctant decision, we were still able to draw meaningful observations from the data we collected. For ease of navigation, we’ve divided our work into distinct sections. The first three rely on data visualizations to illustrate how enrollment trends have changed over time, and to highlight some of the events occurring at our respective institutions leading to, contextualizing, or emerging from those trends. We have also included a collection of links to on-campus organizations at some of our colleges, to raise awareness of what social, administrative, and educational resources are available.

Why did we do it?

Stories matter. National and institutional statistics about student diversity, enrollment, discrimination, and graduation are important, and a lot of useful things can be done with them. But on its own, that kind of data is just numbers, and its difficult to connect to numbers. But people like narratives, and in many ways they can have a greater impact on individual perception than any amount of statistical analysis. We wanted to find a way to turn data dominated by numbers into something that tells a story, and places those numbers in their historical context. We also set out with the explicit goal of creating something useful–a nebulous goal to be sure, but one we believe we have accomplished. The different visualizations, analyses, and resources below are intended to contextualize lived experience. Though our scope is limited due to only having a few weeks to assemble this project, they point towards further questions in need of answering, college-specific support networks, and educational resources for anyone wishing to learn more about BIPOC representation and experiences at our respective institutions.