“Woman has arrived on time with her broom, dust pan,

and scrub brush and her determination that politics must be clean.”

(The Carletonian, October 1, 1924)

We’re a group of students from a collection of colleges taking LACOL’s Summer 2021 Digital Humanities class from a wide variety of majors and backgrounds. As our final research project for this class, we decided to focus on the topic of the 1920’s Women’s Suffrage movement and the reaction to that movement on our college’s campuses. It is a topic that all of us have either previously studied or wanted to explore in our individual colleges’ collections and archives. We wanted to see if bringing together research from individual college campuses would answer broader questions about the societies in which they were situated. Could synthesizing artifacts from disparate communities reveal richer nuances of each campus?

In approaching this topic, we decided on a broad and exploratory research question of “Did different campus environments/demographics have significantly different conversations about the Women’s Suffrage movement?” In an attempt to answer this, we have examined the following five colleges:

- Bryn Mawr College

- Davidson College

- Carleton College

- Vassar College

- Swarthmore College

This array of schools includes several of our home institutions, enabling individual team members to bring their own background knowledge of their campus community(ies) to the table. We have also selected schools with a variety of gender compositions in the early twentieth century, with some co-educational (co-ed) from their founding, some barring women from study entirely, and some exclusively allowing women’s admission as their credo. Our final project serves to bring these various colleges together via an Omeka gallery, visualizations produced by Voyant Tools, and written analysis and interpretation.

Here is a link to our Omeka gallery, an exhibition tool that houses all of the sources accumulated in the exploration of our thesis. You can click on individual sources to see the source in its entirety and learn about the publisher, date, and a small description.

Visualizations

We conducted the majority of our analysis via Voyant Tools, “a web-based text reading and analysis environment […] designed to facilitate reading and interpretive practices for digital humanities students and scholars as well as for the general public” (“About” Voyant Tools Help). We each completed several visualizations and originally produced a total of thirteen visualizations. We’ve condensed that number down to those available below, which we feel accurately represent much of our research.

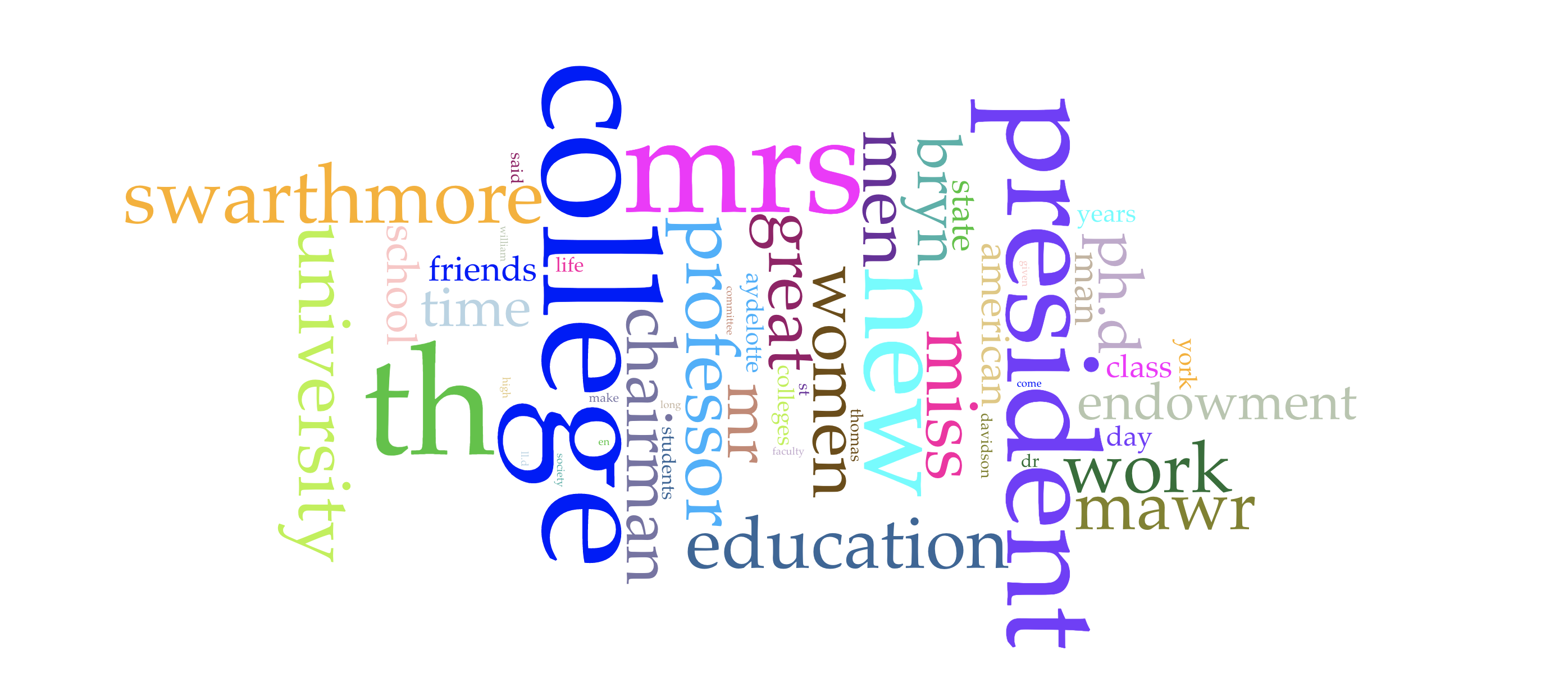

Combined Visualization

This visualization comes from a combination of all the individual sources combined into one corpus. All the sources we used deal with suffrage, but it’s interesting that the word itself doesn’t appear in this word cloud. Also of note, it’s difficult to tell, but the word “men” is mentioned once more than “women.” The “women” count is sixty-nine (69) and the “men” count is seventy (70).

Swarthmore Visualization

The document we chose to assess from Swarthmore was a collection of speeches given at the inauguration of President Frank Aydelotte in 1921, a prominent moment for speakers at the community to reflect on the last several years of Swarthmore and the United States’ history. (There are few documents from this period at Swarthmore—such as college newspapers or yearbooks— that have been made machine readable. While this document is not student-created, it still features discussions of life at Swarthmore and the impact of its role as a coeducational school.)

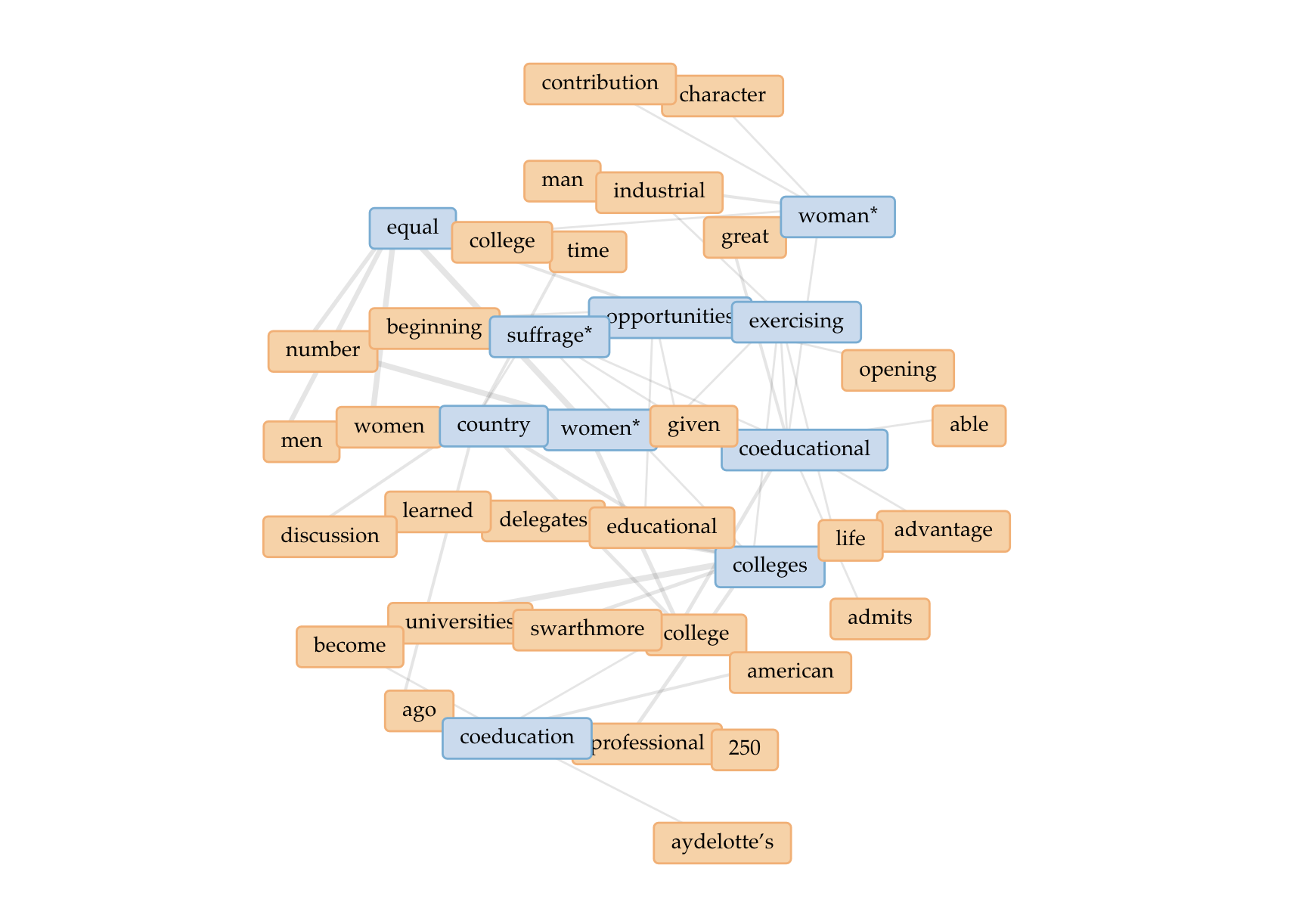

The Collate Link tool provides a helpful visualization of keywords across the speeches.

Many mentions of women were as part of the phrase “men and women” as speakers discussed either the student body or more broad conversations on life and academia—this is evidenced by the bold line between “women” and “men”—but discussions of “suffrage” were quickly linked to coeducation. The gender equality of a Swarthmore education in the early 1920s, at an institution that enrolled equal numbers of men and women each year, was seen as in-line with the national Suffrage movement to provide white women with the right to vote in national elections. The speakers also tie these ideas into national narratives of progress prevalent at the time, with these words linked to ideas such as “development”, “industrial”, or “contribution”.

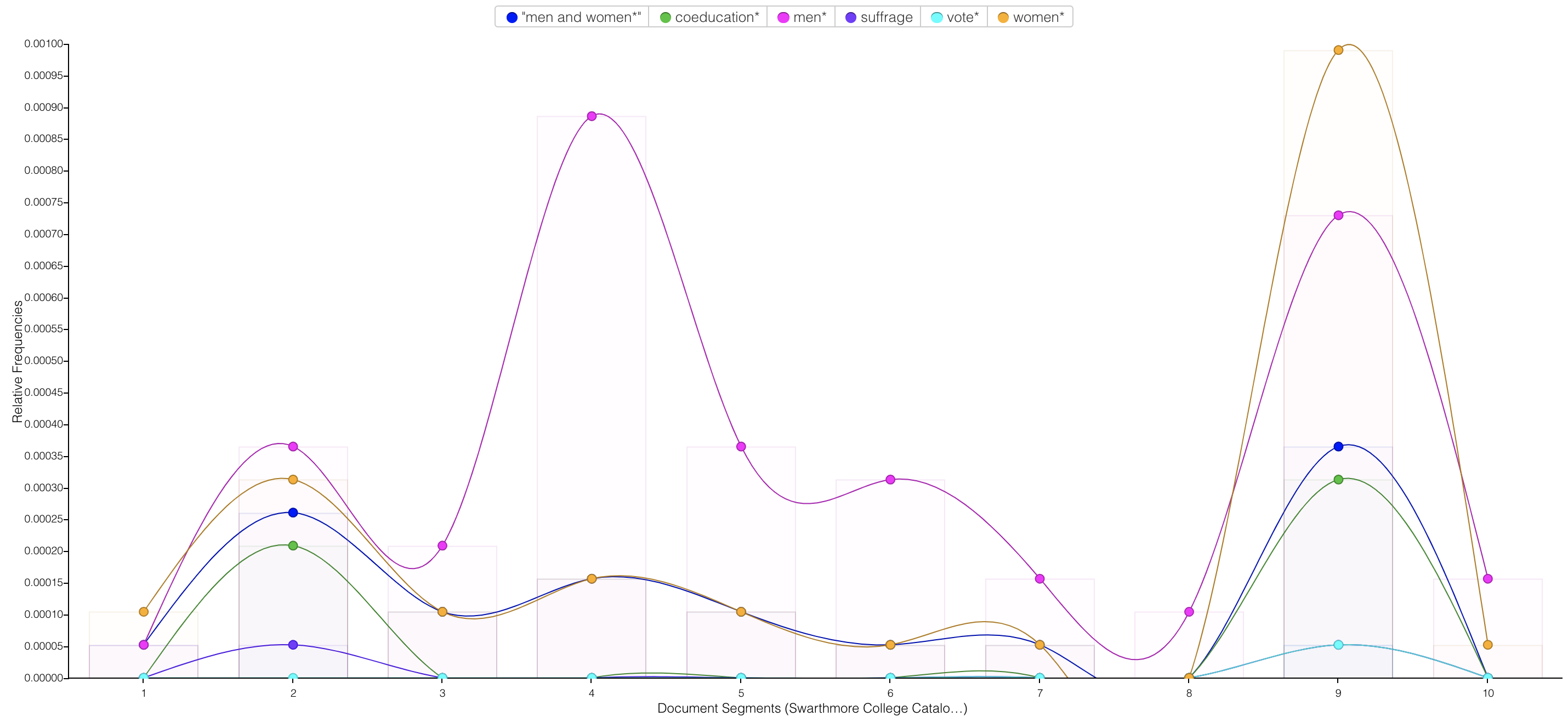

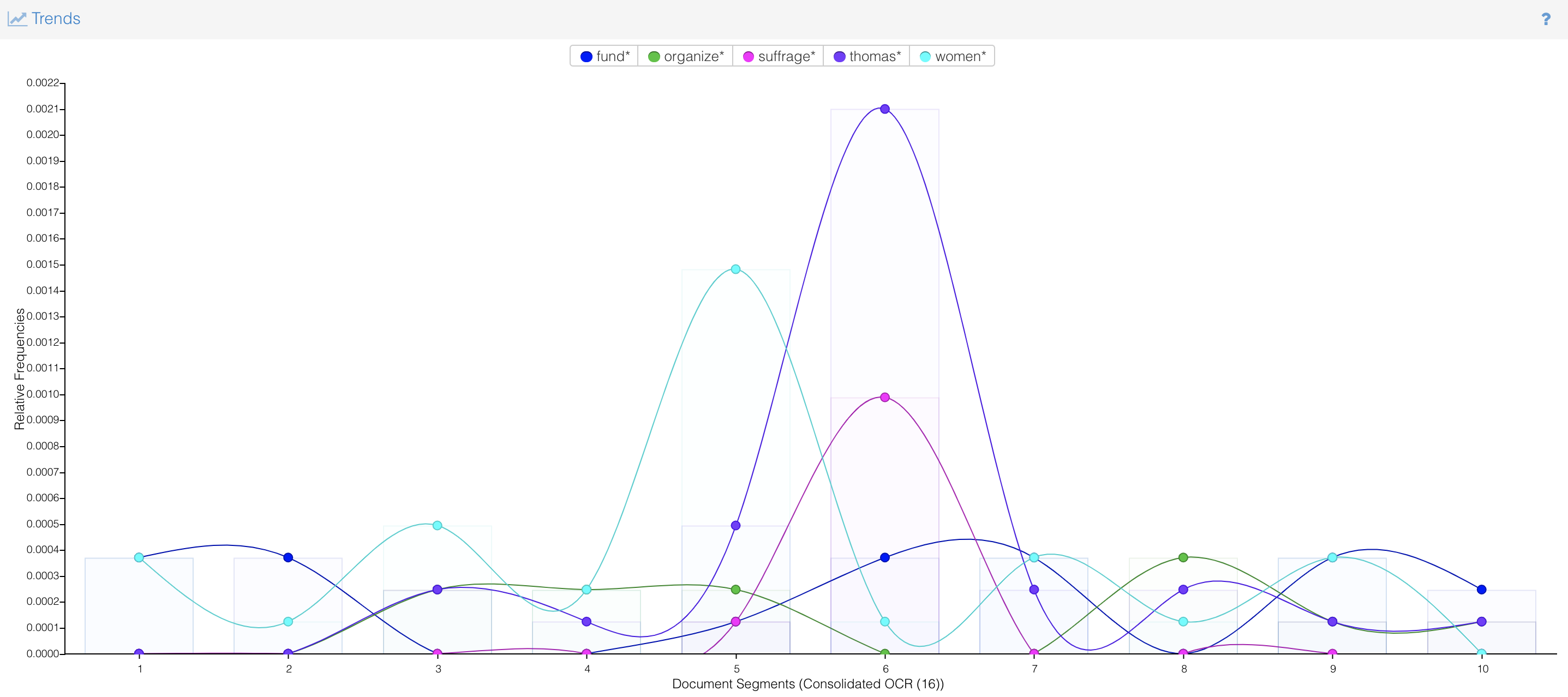

The Trends tool is also helpful in mapping out when a speaker might be speaking more broadly about the “men and women” of Swarthmore College versus when they might be speaking about the push for women’s voting rights.

Here, we can track the speakers that engage with the recent development of the Nineteenth Amendment, alongside those that might speak about women outside of the simple “men and women” address. It is notable that document segment 9 is a speech by Bryn Mawr College president M. Carey Thomas, who predictably spoke extensively on the topic. Looking at both of the Swarthmore visualizations, they define the campus’s discussions of the suffrage movement in the context of the school’s co-educational identity, and emphasize the ways in which the conversations around suffrage linked up with other nearby (and more vocal) institutions.

Carleton Visualization

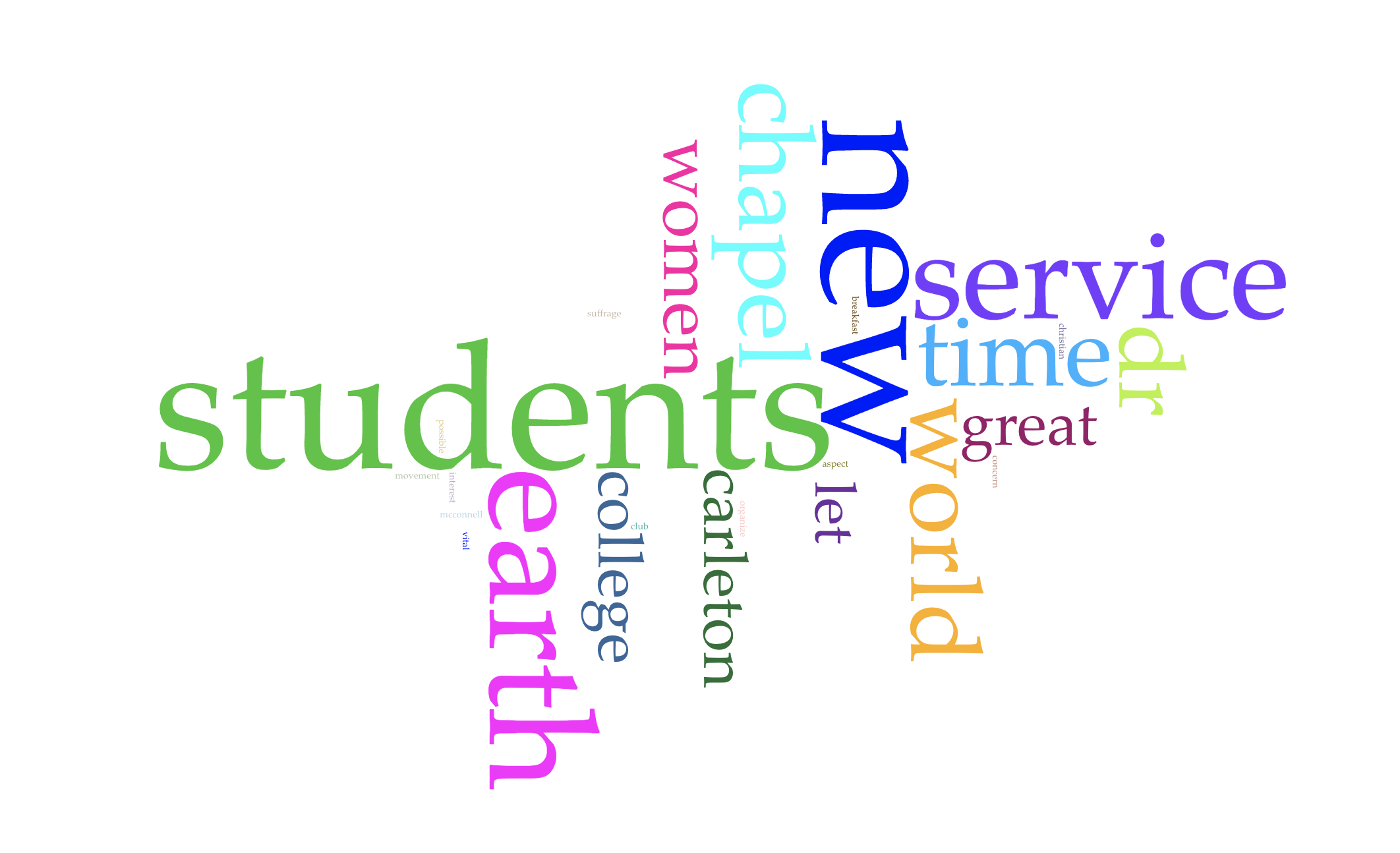

For Carleton, we used several articles from The Carletonian for our exploratory data visualization because we were unable to access full issues of the newspaper from our desired time period. The three articles we chose focus on women’s suffrage and political activities on campus. The Cirrus word cloud indicates the themes that were associated with these discussions around political progress. For example, words such as “movement” and “organize” connect to political mobilization and “new” and “beginning” could potentially connect to changing social values. The Carleton visualizations emphasize the suffrage movement’s place as a political stance, as well as a burgeoning momentum on campus in the midst of larger social change.

Bryn Mawr Visualization

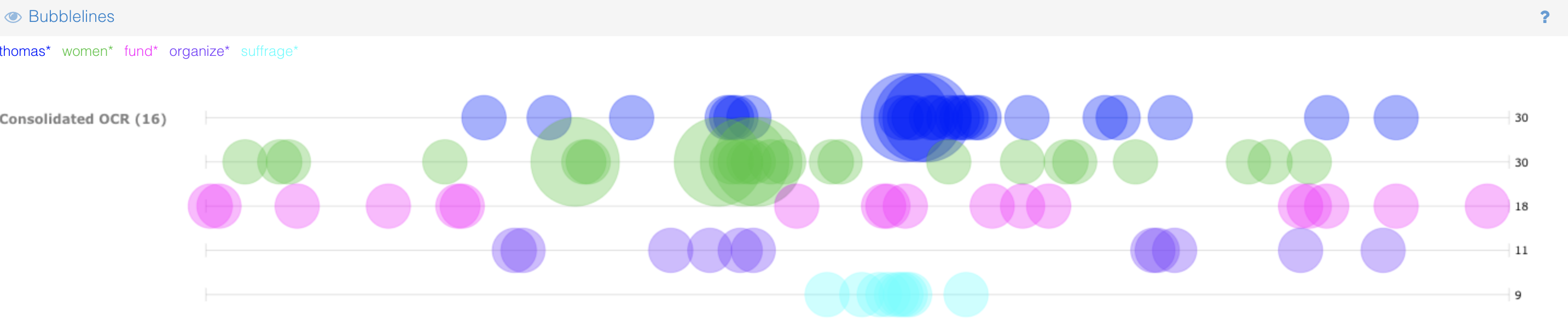

The document we chose to assess from Bryn Mawr was a student-produced and -published newspaper (Vol. 06, No. 14) from January 30, 1920, in which is discussed at length then-College President M. Carey Thomas’ involvement in and campus-wide fundraising to support Suffrage. (Access to the corpus’ entire Voyant Tools interface can be found here.) These two tools (Bubblelines and Trends, respectively) represent the same data but do so to differing levels of effectiveness:

These represent how women are mentioned throughout the publication, as aforementioned, and that the usage of the term does not peak with the mention of suffrage (see: Bryn Mawr College, as HWC). They also show that Thomas’ mention, in this issue, peaks at the same document segment as that mention of suffrage, along with the term “fund.” Any term related to “organize,” “organization,” “organizing,” etc. is absent in this document segment, however. This phenomenon might bring attention to the forms of aid to the women’s suffrage movement in which Thomas was interested or with which she actively engaged the campus population of Bryn Mawr College. These visualizations reveal the focus on high-profile individuals in the movement on Bryn Mawr’s campus, as well as the ways it manifested itself potentially beyond the political sphere.

Vassar Visualization

For Vassar, we looked through publications of The Miscellany News, Vassar’s student newspaper, to find articles that discussed the suffrage movement at Vassar. In this article, “Why Taboo Suffrage?” students who supported suffrage (which was an overwhelming majority) questioned the administration’s decisions to keep the students uneducated about suffrage and politics in general. With some of the more popular words being “women” and “question,” as shown in this cirrus, it is clear that the theme of this article centers around student pushback. Other words such as “opinion,” “realize,” “organizations,” and “intelligent” hint that Vassar students were acting more independently from the wishes of the administration. However, despite being an all-women’s college, Vassar’s administration seemed to avoid the topic of suffrage and while they didn’t actively discourage the movement, the administration didn’t seem to actively support it either. Therefore, it can be inferred that students organized groups and meetings on politics and suffrage to supplement this missing education. The Voyant visualization illuminates how Vassar students took matters into their own hands to educate themselves on suffrage, generate support for the movement, and organize groups and protests for the 19th amendment.

Davidson Visualization

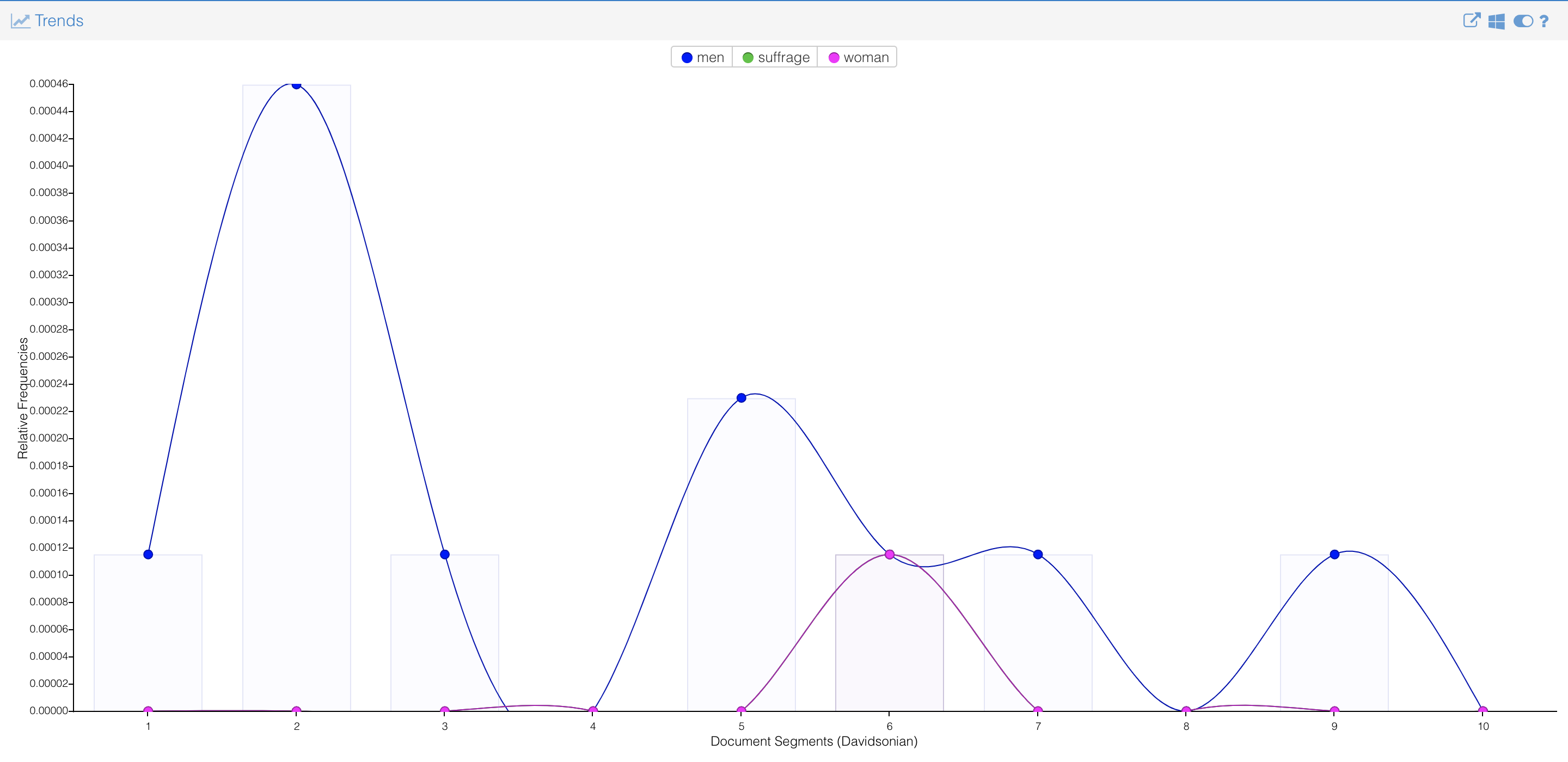

For Davidson, we searched through yearbooks and student newspapers for any mention of suffrage or more generally, women. It’s not surprising that Davidson falls way behind all of the other colleges when it comes to discussing women’s rights. We assume this is because Davidson was all men up until 1972, but we sort of expected women and suffrage to be mentioned more than just randomly in scattered newspaper articles. When suffrage is mentioned, it’s almost always in the comedy section of the newspaper or in the form of a joke. This visualization displays the difference between men and women mentioned and that one spike in the mention of women, shows the reference in the comedy section:

The Davidson visualization emphasizes the ways in which absence is just as telling as presence in collegiate publications.

Intersectionality

We want to stress how the absence of information on women of color in the Women’s Suffrage Movement on these campuses, and likely many others, emphasizes how each of these colleges’ movements centered white women and the opinions thereof and how that illustrates the reality of the white-centered Nineteenth Amendment. None of our sources included discourse on the intersection of women of color and their fight for suffrage and enfranchisement nor the represented college students’ own privilege as wealthier and educated white individuals. Following the same train of thought as that used to discover that schools with all-women demographics were more concerned with Women’s Suffrage, we can conclude that these colleges’ likely small (if not entirely absent) populations of students of color caused the neglect of intersectionality in student conversations. While the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment served as an improvement of women’s rights, the exclusion of women of color in the Amendment further demonstrates how women of color have been historically neglected by white women.

In Conclusion

Our Voyant data visualizations confirm our thesis that schools with different student demographics had very different dialogues around the Women’s Suffrage Movement. We found that all-women schools mentioned suffrage most frequently in their newspapers, while Suffrage was mentioned with lesser frequency in newspapers affiliated with co-ed and all-male colleges. We have also found that the contexts for the discussion around Women’s Suffrage varied depending on different campus histories and social environments. It was telling when specific campuses would publish material related to one topic or another, connecting their perspective on Suffrage to topics that have deep throughlines with their institutional history. An example of this observable in both our data visualizations and gallery items is the Quaker colleges’ (Bryn Mawr, Swarthmore Colleges’) active devotion to peace on both national and international stages in the wake of World War I.

We also were able to use these distant reading tools to notice the absence, especially in the case of mentions of the enfranchisement of minoritized groups that were essential to larger national discussions of voting rights in the United States. (In some documents’ cases, they are even explicit in the discussion of their institution’s celebration of only white women’s enfranchisement.) This may not necessarily mean that those intersectional conversations were not happening, but it is, at the very least, significant that they did not find themselves represented in their institution’s archival records and digital collections.

If we had more time or if any one of us wants to continue exploring the thesis of and materials collected for this project in the future, our next step would be to explore trends in item metadata utilizing OpenRefine, “a powerful, open-source software which visualizes and manipulates large quantities of data all at once” (“About OpenRefine,” Illinois Library). While we centralized our efforts more in Voyant Tools than OpenRefine, cleaning and organizing our data to obtain a “big picture” view of the sources might have led us toward other helpful and enlightening visualizations.

Sources

Authors

Wren Jackson, Bryn Mawr ‘24

Lily McDonnell, Vassar ‘23

Beck Morawski, Bryn Mawr ‘21

Gemma Null, Carleton ’22

Emily Schmitt, Davidson ’23

Advisors

Nhora Serrano, Associate Director for Digital Learning & Research, Hamilton College

Marcella Lees, Carleton ’21