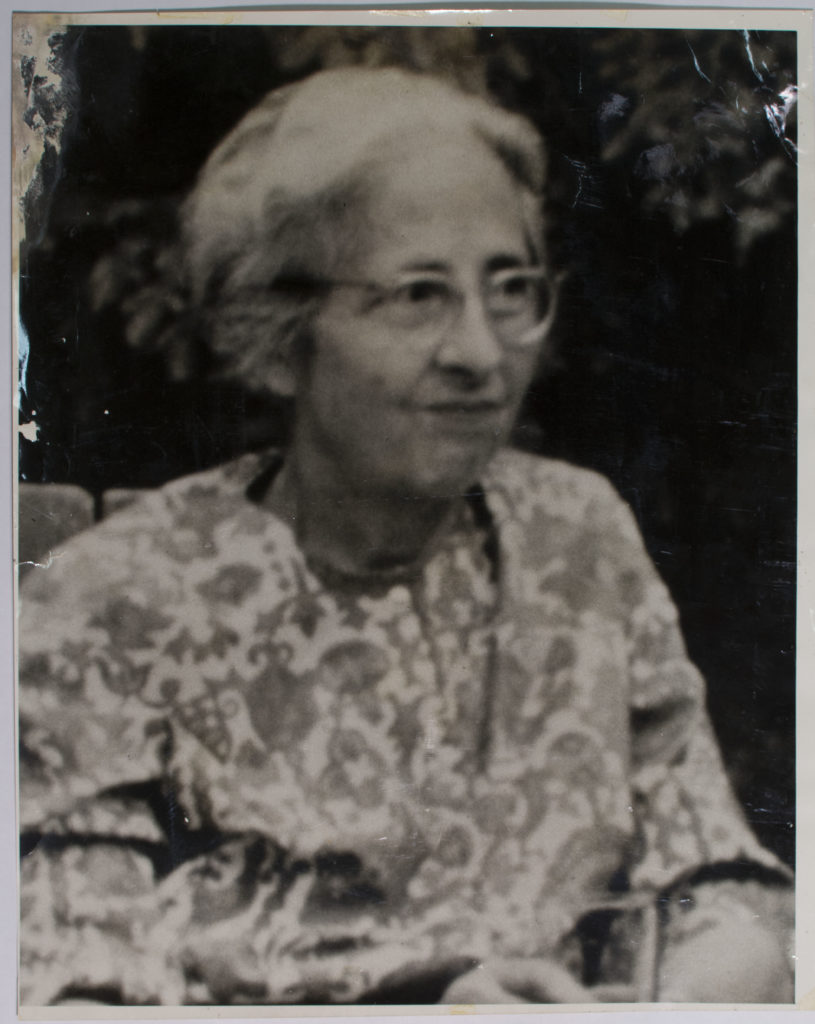

Margaret Ralston Gest grew up on the City Line of Philadelphia. Born in 1900, she attended the Agnes Irwin School in Rosemont and developed an early appreciation for birds, flowers, and her parents’ library. While completing an art degree at the Philadelphia College of Art, Gest spent summers studying under Hugh Breckenridge, an experimental modernist painter, in Gloucester, Massachusetts. After graduating in 1924, she traveled Europe to paint; in Paris, she furthered her art education with classes at the l’Académie Scandinave. Throughout her career, Gest showed her work annually at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts as a Fellow. On several occasions, she showed with the Philadelphia Ten, a group of female artists who collectively exhibited their work in the United States between 1917 and 1945; critics of her inclusion in one show noted she was considerably “more modern” than the Ten. Gest’s interest in religious studies led to several publications, including a translation of Latin poetry and an edited volume of 17th-century English cleric Jeremy Taylor’s sermons and devotional writings. She actively produced artwork until about 1950. She spent her final years engaging in philosophical conversations with her partner Miriam Thrall and tinkering in the garden of her family home, where she passed away in 1965.

“Head in Light,” self-portrait, HC09-4894

Gest showed at a special invitation exhibit of the Art Alliance in October 1945. Gest rarely did portraits, making this self-portrait quite unique. Of her work, an art critic for the Philadelphia Inquirer wrote “near at hand is Gest’s self-delineation “Head in Light,” one of the few portraits she has ever painted. The touch of color on the tip of the nose probably means more than meets the eye.”

As an artist, Margaret Ralston Gest defied categorization. Her mentor, Breckenridge, was himself shifting styles – from neo-impressionism to abstraction – during the period Gest studied with him and that fluidity was absorbed by his pupil. Her watercolor landscapes, the medium and theme on which she most often focused, exude light, color, and motion and are recognizable as hers by the distinctly loopy trees dotting hillsides. In contrast, the colorwork of Gest’s oil canvases reflect American tonalism while their bold brushstrokes resemble the fauvists at times. Meanwhile, her pastel landscapes focus on industrial buildings and townscapes, more closely resembling the work of American precisionists.

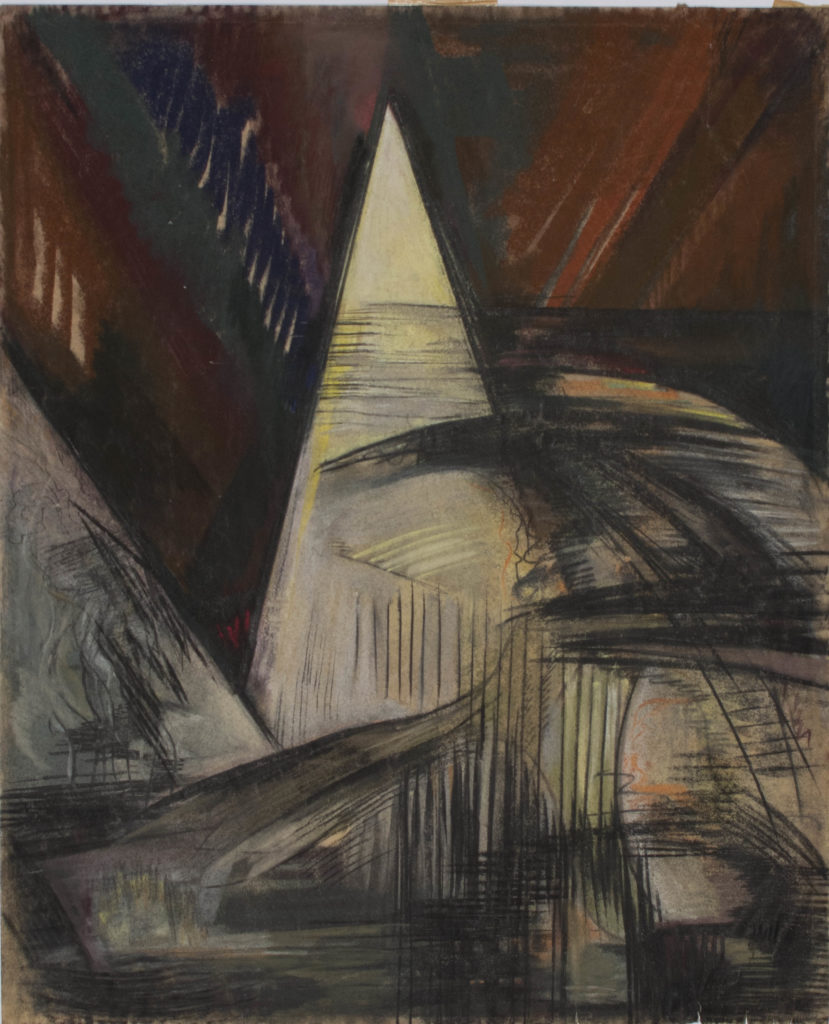

“Guitar in Pastel,” HC2017-0556

“Abstraction,” HC2017-0514

One group of works she never showed publicly were her nudes. In them, her pastel nudes reflect the disconnected lines of the Cubists but lack the contrasting vantage points expected of the school’s masters. Rather, Gest treats her lines and color with enough softness and movement that they hint at the stylized illustration of 1920s women’s magazines.

“Oil of reclining nude,” HC2018-0515

“Nude in Acrylics,” HC2017-0543

As an intellectual, Margaret was encouraged by her parents from an early age to explore their substantial library and she quickly became a prolific reader. Her mother, Emily Judson Baugh Gest, was an active Philadelphia socialite committed to its history through her work with the Philadelphia Society for the Preservation of Landmarks. Her father, John Marshall Gest, an attorney promoted to Orphans’ Court judge during Gest’s adolescence, was called a “student of great novels” by his friends.

Emily Judson Baugh Gest and John Marshall Gest

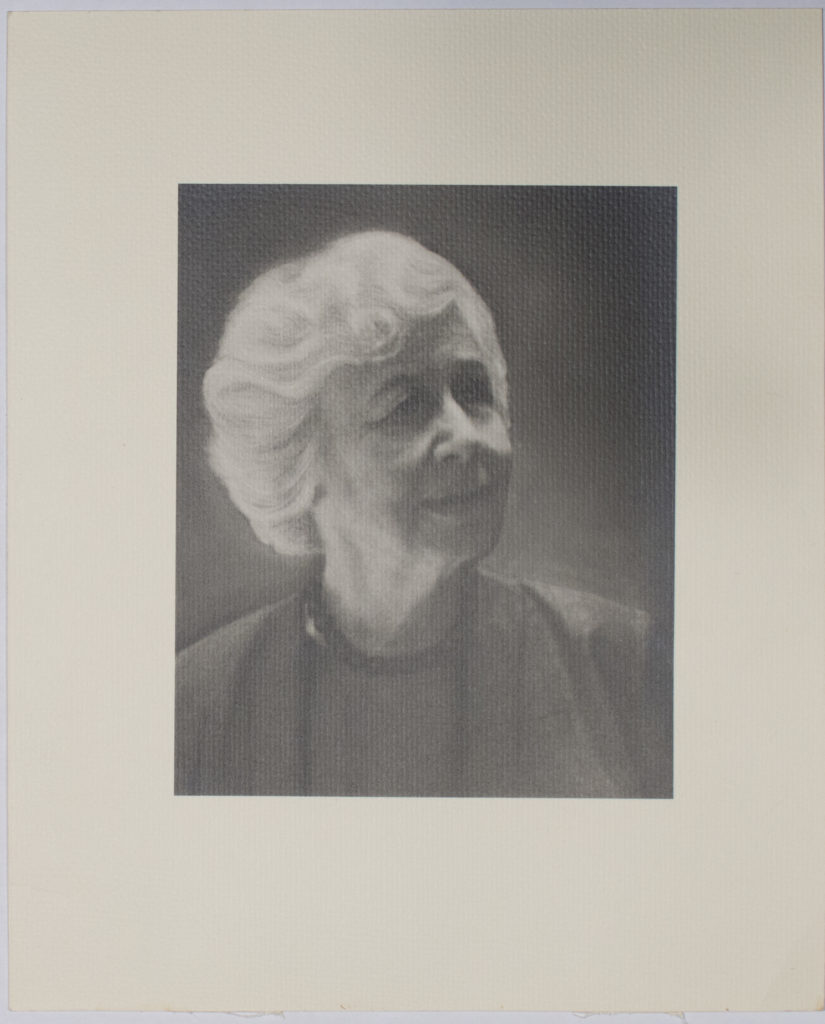

By the mid-1940s, Gest’s interests increasingly turned away from art and toward the theological and philosophical. A great part of this may have been her relationship with Miriam Mulford Hunt Thrall, who held a doctorate in literature from Columbia University and with whom she would spend her remaining years. In her final two decades, Gest wrote poetry, published a translation of 17th-century English mystic Jeremy Taylor’s writing, and completed a translation of Horace’s Odes. At the same time, she began to expand the family library by collecting rare editions of important religious and philosophical tomes, including the 1493 illuminated manuscript Nuremberg Chronicle. Miriam Thrall donated the 3,000 volume collection in its entirety to Beaver College (now Arcadia University) upon Gest’s death in 1965.

Margaret Ralston Gest in her later years

Miriam Mulford Hunt Thrall

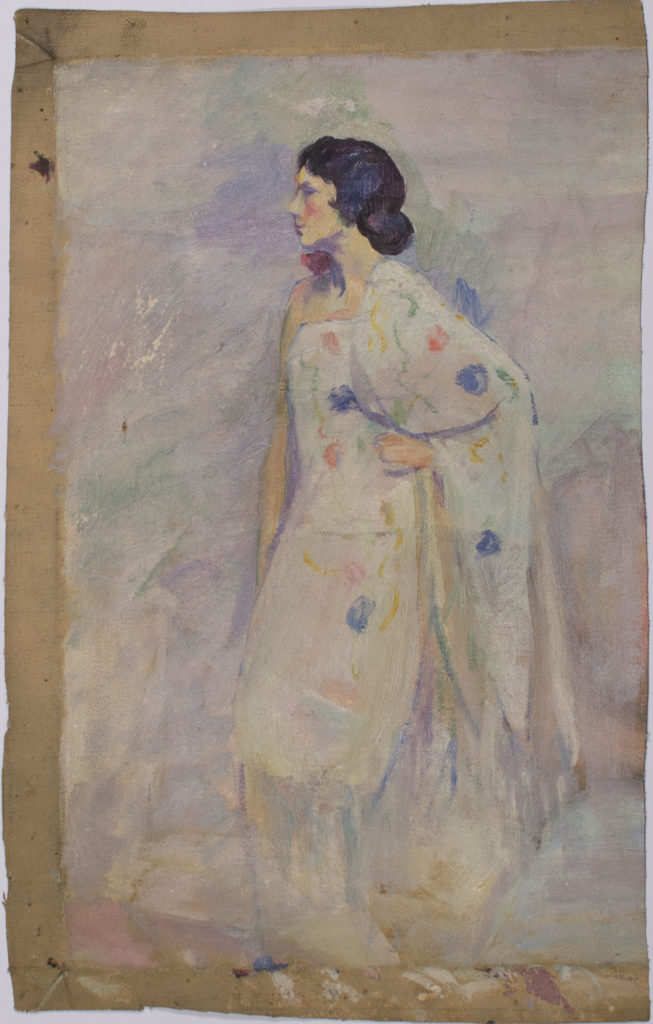

As a personality, Margaret – or “Gestie” as her friends called her – was a feisty, playful woman. Early in her art career, Gest traveled through Europe with fellow women artists, including Emily Smyth Cooper Johnson and, more frequently, Edith Longstreth Wood. Wood recounted a 1928 with Gest in the Bryn Mawr Alumnae Bulletin as “four gorgeous months in Italy, France, and England … The high-water mark may have been Provence, or a motor trip through the Italian hill towns … or painting in Brittany.” As well as travel companions, Gest’s friends made fine models for her work, and surely she for theirs.

“Edith Wood,” HC2017-0598

“Emily Cooper Johnson,” HC09-4412

“Portrait in Oil,” HC2017-0508

When not traveling for her art, she enjoyed spending long hours in her garden where she enjoyed the plants and birds learned about through her beloved books. She was often irritated by students of the neighboring St. Joseph’s University who had a large lawn, adjacent to hers, where they played sports. Their youthful activities disrupted the bird watching and the peaceful gardening she enjoyed – which frequently brought her to verbal blows (which she probably enjoyed at some level) with the student body and administration. However, she eventually conceded to their presence, enough that she sold her family home to them – to be transferred upon her death.

Among friends, her scrappy personality most often manifested as practical jokes. Miriam Thrall recounted a luncheon she and Gest held at their home. Taking a phone call early in the meal, Gest told her friends to continue without her – which they did for the remainder of the lunch. Finally, as the group finished their coffee, Thrall remembers Gest throwing off “her maid’s cap and apron … thoroughly satisfied by the pleasant hour of enjoying her friends and being able to concentrate on their cleverness” without their knowledge.