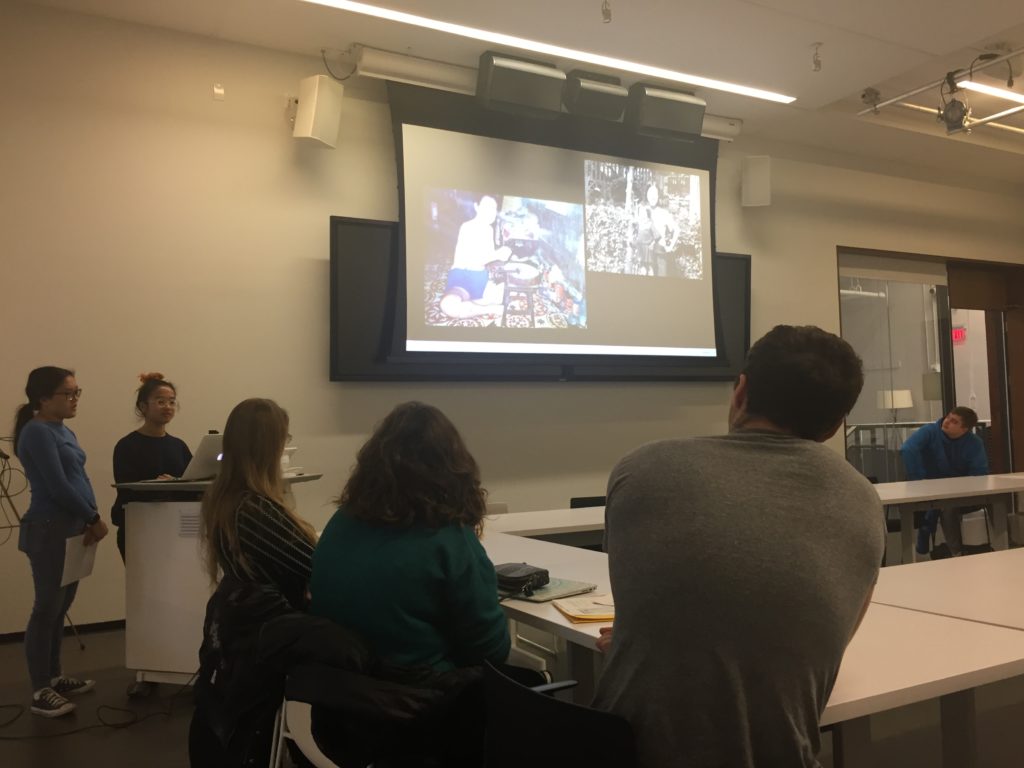

Interviewed by Kaley Liang and Cassandra Manotham

Lived in Cambodia until 1975, fled to Vietnam and lived there from 1975-1983.

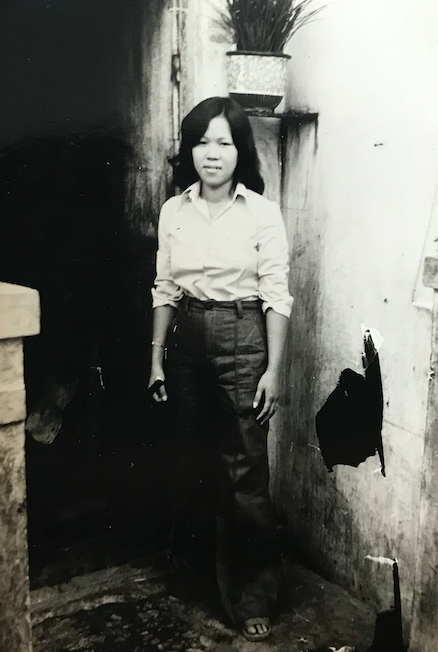

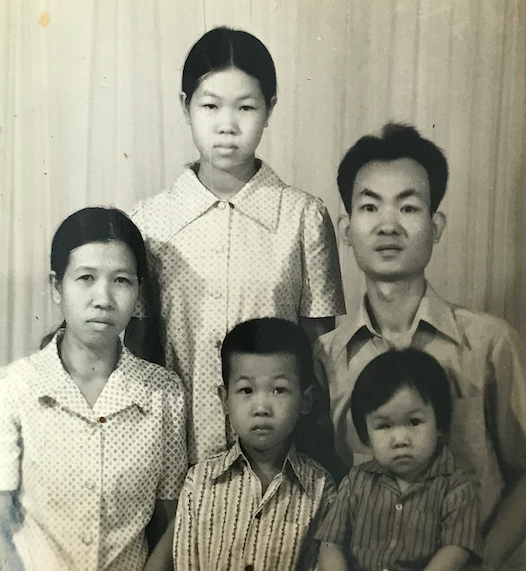

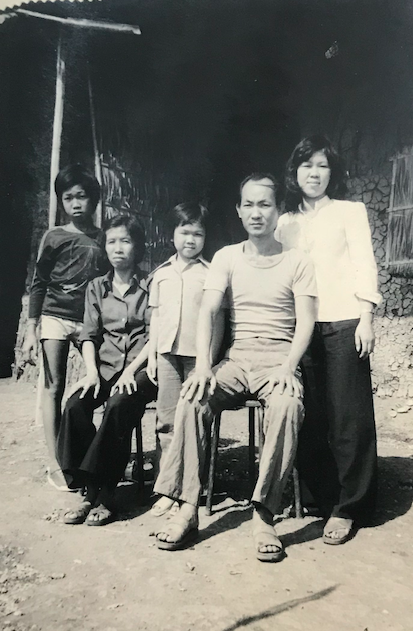

Lisa Chhin is a civilian from Cambodia who fled to Viet Nam to escape the Khmer Rouge genocide. From April to September, her family set out on an arduous journey to post-war South Viet Nam, eventually settling in Tay Ninh. She remained in Tay Ninh for eight years, mainly taking care of her family and the daily household chores, and helping with her parents’ shoemaking business in her free time. Her story speaks to the struggle and resilience that civilians were forced to face within the war-torn countries in Southeast Asia.

Reflections on the interview from Kaley Liang:

What struck me the most about my interview with Lisa was not just the importance of telling her story despite her civilian status, but more importantly, how excited she was to make her story public. It is easy to overlook individuals like Lisa in the broader narrative of the Viet Nam War, instead focusing on those directly involved in the military conflicts or the political decisions behind them. For many, lives like Lisa’s are too quotidian, and the stories they have to tell are simply not worth hearing. Listening to Lisa’s narrative, particularly about her daily life in Viet Nam post–escape, however, showed me the trials and tribulations present in even “everyday” chores. The difficulties Lisa faced in tasks as simple as buying food and cooking a meal for her family taught me that there are stories in every aspect of life, no matter how basic they may seem. This is why even the poorest, most remote civilians affected by the Viet Nam War should be heard from; doing so will create a far richer narrative of a war that historians are still trying to sort through. And perhaps more importantly, doing so will show these “insignificant” civilians that they matter too, and that their stories are valuable to others. At the end of the interview, Lisa mentioned how she had been wanting to make the narrative she had been telling us into a book, but that she felt that she lacked the English ability to do so. She noted how this Oral History Project was an easy, accessible way to make this story known to the public, and even to her step–daughter, whom she has yet to tell her full life story to.

Another lesson I was reminded of by talking to Lisa was the sheer privilege and abundance of opportunities that comes with being an American citizen. It is easy to forget this privilege when surrounded by others are also afforded these same opportunities daily. Talking to Lisa reminded me to consider my life within a global perspective. The hardships I have experienced throughout my life do not even compare to the ones that Lisa has had to overcome, from the death of her siblings and grandmother during the escape from Cambodia, to the poverty she experienced in Vietnam post–war. The positivity and happiness Lisa radiates despite these immense challenges, simply because she now is living in the United States, has really stuck with me, and has inspired me to not take things for granted, even something as simple as multiple brands of rice in supermarkets.

Reflections on the interview from Cassandra Manotham:

It was a remarkable feeling to gain, first hand, the stories from an individual who lived through the period of the atrocities in Southeast Asia. For one, resources are hard to find merely because the United States did a poor job in reporting, accurately information about their presence in Southeast Asia. Moreover, if they did express information, it would be in a Western lens or framework. Therefore, Lisa Chhin, as a woman Cambodian-Chinese-Vietnamese individual, who has lived resiliently enough to tell me her story is absolutely rewarding.

Often when the chance arises to speak to someone who has been through so much struggle and toil, one desires a “one thing you learned from this experience” type of response. At least, that was what I was most eager to hear. In my mind, I thought, if there is anything I can learn about life from Lisa, it must be optimistic. Afterall, she had survived death and persisted through all of the struggles waned against her. However, when I asked this exact question, I was left with “nothing.” Indeed, this was a profound response and quite harrowing. It revealed to me, that even within all of her suffering, there is never anything to be gained from war. To her and many Cambodian civilians, it didn’t make sense. All it did was take the lives of the people she loved and disrupted the country. Nevertheless, I think something in Lisa’s eyes when she illustrates her life in America and the lessons she’s instilled in Kaley and I about never wasting food, I think there is something to be gained from that.

Full research and reflection papers: