When setting out to study the controversies that brought urban planning and indigenous representation under the spotlight in Auckland, New Zealand before and during the 2011 Rugby World Cup, we need to establish methods for making sense of the complex web of actors, events, ideas, experiences, and environments (natural and built, existing and imagined) that, we will find, defines that time and place. To accomplish this, we adopt methods for practicing urban ecology that are based heavily on the work of Bruno Latour and uses an actor-network theory framework that overcomes reductionist tendencies in ecology by embracing complexity of networks and heterogeneity of actors and realities.

Ecology as a practice is traditionally rooted in a biological approach to understanding living beings, their environments, and the complexity of interaction that exists between those actors. For this reason, a definition of ecology frequently features terms like “organisms” and “physical surroundings”, and ecologists have often assumed a framework of naturalism when attempting to explain complex systems, meaning that ecosystems are treated as a function of the natural world that are primarily or entirely the product of natural laws.

So, for many scholars, “urban ecology” is simply the practice of biological ecology in the context of urban or urbanizing ecosystems (that have for the most part come to be dominated by humans) to study the way humans and ecological forces of nature interact. When the term “human” is used in contrast to “nature”, as is the case for one definition of this field found in the journal Urban Ecology, a categorical distinction between humanity and the rest of nature is presupposed. Not only does this assumed separation ignore the biological reality that humanity is a product of natural evolution and an inextricable element of nature, but it also fails to critically examine the assumption that a single objective natural reality exists outside of subjective human experience

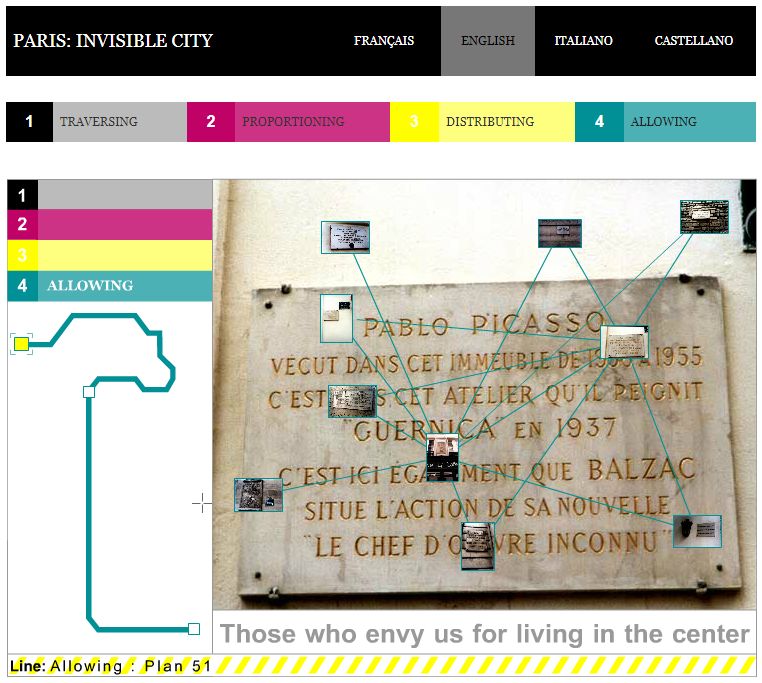

However, the field of urban ecology includes a diverse range of interdisciplinary approaches, and in this project, we choose to take one such social scientific approach that is informed by anthropology, ethnography, and sociology. We believe this approach is better equipped to deal with the complexities and conflicts of urban planning controversies, bicultural politics, indigeneity, and a litany of other non-biological or even intangible themes that are of vital interest to our study of Auckland. To develop this approach, we first need to be critical in defining key concepts like “city” and “actor”, avoiding the tendency to equate the former with “non-actor” or “background” and the latter with “human” or “organism”. Latour addresses the issues of these definitions in “Paris, invisible city: The plasma” (2012), in which he argues that the city is neither a passive backdrop against which humans act nor is it easily simplified into a presupposed relationship of parts to whole, be it in a geographical, biological, social, political, or other context.

Instead, Latour claims that the city is only understood in its multitude of actors, relationships, perspectives, and realities taken together holistically. To accomplish this, Latour hypothesizes the plasma as a metaphysical space in which the diverse elements, interactions, and realities of the city are composed and constantly shift in relation to one another. All the connections and structures that define the city—be they visible or invisible—are held in the plasma. In describing the city as fundamentally a complex web of invisible relations, Latour develops an actor-network theory of ecology. In actor-network theory, the world in its many dimensions is modeled as a network of relationships between heterogeneous actors, including humans, spaces, ideas, etc. in which everything, material and immaterial, is related and interconnected. Our purpose, therefore, is to make visible the invisible Auckland that hides in the plasma.

Because of the inherent complexity of this model of urban ecology, Latour’s concept of the oligopticon also proves useful. Latour’s oligopticon is a tool to see, understand, or exert control within a very limited scope, producing a “sturdy, but narrow view” (Latour, 2005: 181). An oligopticon can be a photograph, a map, a painting, a private journal, a scientific experiment, a newspaper, etc. These diverse windows into human experience, far from objective or totalizing when taken individually, collectively offer a way to pierce the veil of the plasma and understand the complexity of an urban ecosystem.

Oligopticons are not homogeneous and none of them exist outside of the network itself. In fact, Latour’s oligopticons are sites where social and ecological structures are themselves created, such as bureaucracies, courts, voting booths, and laboratories. This fact is particularly relevant to our attempts at understanding the diverse interests and conflicts that took shape in Auckland because our best tools for understanding Auckland were themselves involved in the political and physical shaping of the city and demand a diverse composition.

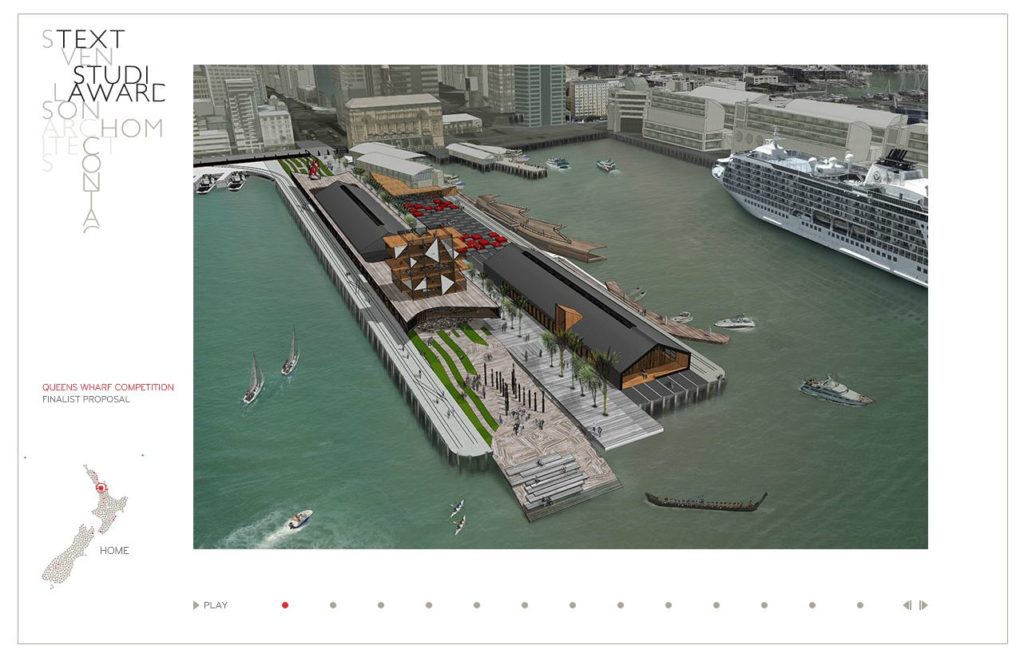

For example, we can understand something about the Queens Wharf design competition by studying the official website that announced the start and later cancellation of the competition, but the resulting view of the controversy would be incredibly narrow. Despite that limitation, the solution is not to discount the oligopticon-view provided by the website but rather to contextualize it alongside the perspective of a multitude of heterogeneous oligopticons. This might mean including architectural designs submitted by Māori architects imagining Queens Wharf as a Māori meeting house, the words of politicians vying for power in the newly announced Super City governmental structure, the protests by Māori activist groups demanding better representation in decision-making bodies, and photographs of the structure that was eventually built on the Wharf, among uncountable other possibilities.

By adopting Latour’s hypotheses of the “plasma”, “actor-network theory”, and the “oligopticon”, and by avoiding reductionism, we develop a method for studying urban systems that allows us to embrace complexity and the multitude of coexisting or conflicting realities that make up an urban system. In the case of Auckland, this method allows us to visibilize the actors, spaces, experiences, and ways of being that are often forgotten, simplified, disenfranchised, or colonized. Crucially, it empowers us to see how these invisibilized elements nevertheless always remain a vital living element of the urban network and time and time again challenge the city to reckon with itself.

By Ben Paul