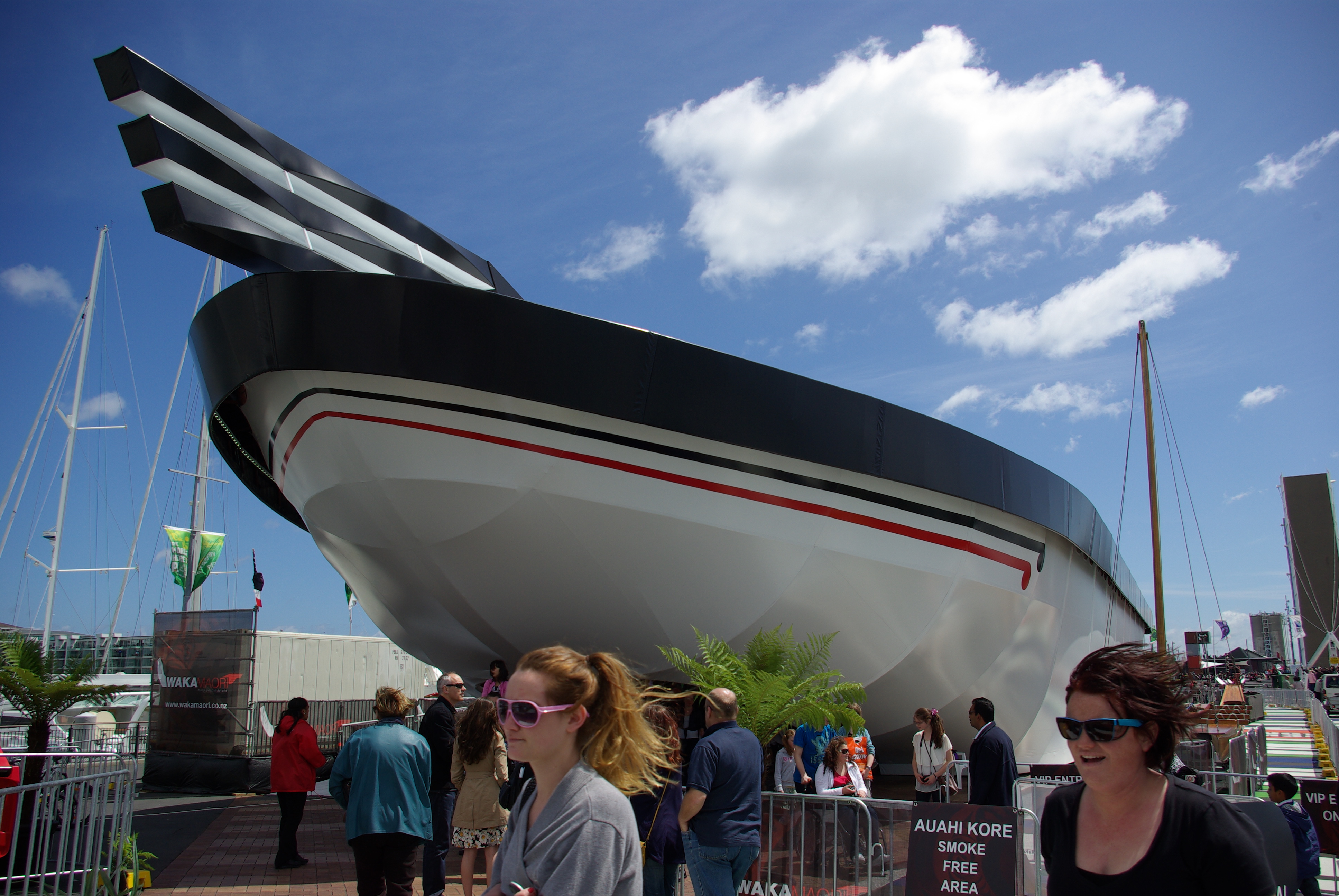

On April 6, 2011, news broke of a new project aimed to closely link Māori culture with the upcoming Rugby World Cup in Auckland. The national government and the Ngati Whatua o Orakei hapū planned together to construct The Waka Māori, a space for 11 days of events contained within a 60-meter plastic tent shaped like a waka (traditional Māori canoe). Like the larger “Party Central” development at the nearby Queens Wharf, Waka Māori would be filling in an otherwise underutilized waterfront space at nearby Te Wero Island. The project quickly came under fire as it was revealed that the hapū, who would own the structure, would only contribute $100,000 to the project and the rest of the $2 million would come from government funds. Labour Party MP Shane Jones established himself as one of the most outspoken opponents to the development, decrying the “tupperwaka” as an enormous waste of money and an embarrassment to the Māori. And yet, other Māori continued on with their support, including Minister of Māori Affairs Pita Sharples, who contextualized the project in concern for a lack of Māori visibility: the America’s Cup yacht race, the last major international event in Auckland, had also been a multi-million-dollar production with little to no Māori representation.

The project continued to be divisive in public opinion as its development timeline proceeded, and even Māori opinion could not be unified on a project meant to celebrate their culture. The extensive use of public funds brought attention to the matter of who Waka Māori would truly serve. While it can be said that the fact of Māori representation in the Rugby World Cup is the greatest benefit of all and one with universal value toward advancing New Zealand as a bicultural nation, the material benefit was much murkier. Many expressed their frustration at having their tax money go toward a project which would be privately-owned, and this was only amplified by the opaque development process. A full two months after news was broken of the development, the budget became public knowledge – $900,000 would go toward construction and $1.1 million toward funding its cultural programming. The $300,000 provided by Prime Minister John Key toward the event bred controversy as it was speculated to be a political stunt, one which would help to secure his favor among the influential hapū. Other sources of funding also stirred public concern. Ngati Whatua o Orakei heritage manager Ngarimu Blair had been heavily involved in developing the project and overseeing its budgets when the news broke that events management company Evitan Events, owned by his brother Renata Blair, would be subcontracted with the operations budget. The New Zealand Herald reported that this contract was likely worth up to $300,000.

The Waka Māori ended up as a $2 million project for only 11 days of programming, starting on October 13, 2011 and concluding on October 23, 2011. As the day approached, the hapu began to raise concerns that their $100,000 investment in the project would be lost or break even in the best-case scenario, casting some uncertain gloom. All 11 days would be entirely populated with Māori cultural entertainment, including dancers, musicians, rugby legends, and Māori craftsmen demonstrating traditional production techniques. Speakers such as Prime Minister John Key would provide nighttime addresses at specialized receptions, including one on the opening night for international press. When opening day arrived, around 21,000 people passed through the doors of the waka before its close. This rate quickly increased over the span of its programming, and by the final day of Waka Māori programming, an estimated 400,000 visitors had engaged with the space and its entertainment offerings. The hapu’s gamble had paid off and Waka Māori successfully became one of the most popular features of the Rugby World Cup, despite all the negative press and uncertainty around the ethics of value of its development. A report by Te Puni Kōkiri released after the Waka’s closing sang its praises, reporting high overall visitor satisfaction and a boost in consumer spending of about $9 million – 4.5 times the money put into its development. Waka Māori now still remains in the hands of Ngati Whatua o Orakei and can be shipped to another locale and reinstalled whenever needed, extending its life beyond the original 11-day event. In 2013, for example, the waka was transported to the 2013 America’s Cup in San Francisco for display.

Much of the questions which originally brought about concern with Waka Māori may continue to go unresolved. Māori opinion, of course, is not monolithic, and no one Māori’s opinion can represent the entirety of the people nor even a single hapu. Whether it was appropriate for the government to cover so much of the cost for this, also, is not so clear – however, it is indeed in line with the ethos of extensive government financial support for the private competition of the Rugby World Cup, as with the Queen’s Wharf redevelopment project. In this case, though, the matter of commodifying long-held traditions further complicated the governmental support. Perhaps the entire practice of public-private subsidy like this ought to be taken into question, rather than this individual case. Was the government complicit in turning Māori culture into something to be sold and consumed by tourists, rather than something to be internally shared and experienced by Māori? How can the project leads, who were mostly Māori, square this question with their own experiences in Māori culture? If this is indeed inappropriate, then what is the best option for ensuring the longevity of Māori culture?

By Simon Balukonis