This project aims to investigate the intersection between the political controversies of the Maori perspective on the taniwha and their interactions with proposed architectural schemes, from the perspectives of two classes.

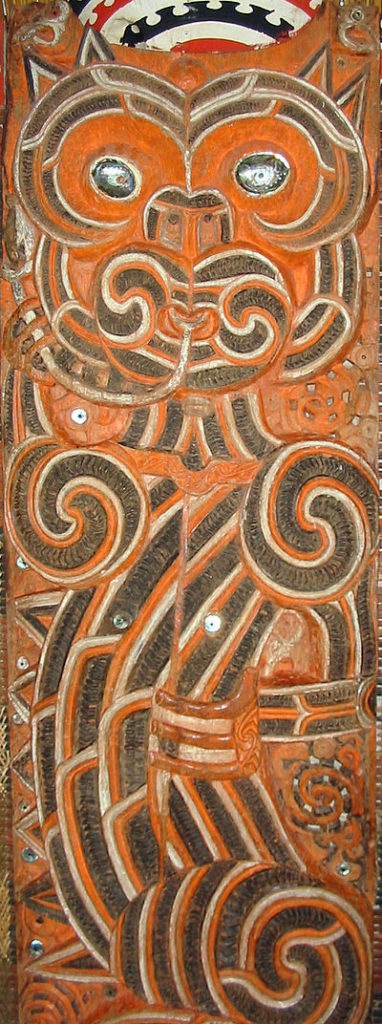

Taniwha roughly translates to “supernatural water dragon” that resides around or within a specific natural water site. These creatures are an integral aspect of Maori culture, that possess various roles such as protective guardians, dangerous beasts and even predatory beasts. The sex of the monster may be either male or female, with each kind of Taniwha associated with different tribal groups, while the concept has long been used to “indiginize” New Zealand’s approach to political issues and increase representation.

In 2011, a new City Rail route was proposed to go under an old stream that ran beneath downtown Auckland. The city’s seven districts and councils had been transformed into one super city council. During this transition, Auckland gained two things: the Independent Maori Statutory Review Board and the ability to successfully plan large infrastructure projects.

Glen Wilcox, member of the Maori advisory board proclaimed in a Council meeting that the proposed subway route would cut across the old underground stream, wherein dwelled a taniwha— “a guardian dragon”, called Horotiu by the Ngati Whatua who had not been consulted. Continuing the project may have caused an environmental disaster. According to Wilcox, council officials failed to consider the interests of Maori people.

Although previously considered a sea monster, interestingly a veteran of Maori Studies Ranguini Walker claims that the taniwha may be a “coping mechanism” for the Maori, as people use them to explain events and attribute them to certain actions. Interestingly, a number of similar controversies surfaced with regard to disputes between the Maori people and infrastructure proposals. For instance, the Ngawha Prison (around the Nagwha stream) instigated locals as it was believed that a taniwha resided in the water body. A report on the incident described the stream as being the “spiritual backbone of the prison”, thus requiring careful cultural and political planning of the development of this building.

From the perspectives of indigenous representation and urban ecology, we will explore the trajectory of Maori issues in New Zealand, through essays on the subject of Taniwha.

By Riya Philip