One of the ways that we have learned everything we know is through experts and figures of authority. In almost all science classes, we know what we are learning to be true because in expert in the given field has proven it. We learn a lot about ourselves through experts; we rely on our dermatologists to tell us what a certain rash is caused by, we rely on a psychiatrist to determine if we have a mental illness, we rely on a pediatrician to tell us what medicines will help our children to recover quickly, we rely on nutritionists to tell us what foods we should be eating, and we rely on our orthodontist to instruct us as to what will help our teeth and mouths. We even rely on others to tell us the date of our birth. Virtually all of the information that we receive is at the hands of experts, unless we have personally observed it. We know the structure of DNA because of experts, but we know that the sky is blue because we are able to personally observe it (Goodwin, 2011).

An expert opinion, or an appeal to authority is often used for the basis of an argument: if someone says “x” is true, and that someone is an expert, then “x” must be true (Doos, n.d .). In other words, the arguer argues that he is right because he has the opinion of an expert.

This argumentative technique is correct when appealing to an expert in the field that you are arguing about; for example, when speaking about ones mental illness, appealing to a psychiatrist would be logically correct and not fallacious, and when speaking about ones teeth, appealing to an orthodontist is also not fallacious. So, because virtually all of the information that we know to be true is proven through experts , there are some facts that can be argued based on the fact that an expert has proven it to be true, or more generally speaking, said that it was true.

However, appeals to authority and expert opinion are considered to be logical fallacies (Goodwin, 2011). When one appeals to authority, but the subject that they are speaking to is outside of that authorities field of expertise, it is fallacious. An experts opinion is only to be appealed to in the field that they are an expert in; for example, an orthodontist cannot be relied on to give patient information about their mental illness, and a psychiatrist cannot be relied on to give information about their patients’ teeth and mouth. So, the fallacy occurs when a figure of authority is appealed to just for being a figure of authority; Dr. X says it is true, so it must be true, regardless of what “it” is (NG , 2014). In other words, authority A believes statement or claim B is true, and B is outside the scope of practice or relevant to the subject X . Therefore, B must be true (NG, 2014). Furthermore, an expert is not right 100% of the time, and they are not without biases (Doos, n.d.). This is the problem; in almost all areas of our lives, we rely on experts to give us the information that we need, but there are times when experts cannot be trusted; it is important to be able to recognize those times when making an argument, and when listening to the arguments of others. As defined by Douglas Walton, it is questionable whether “the individual thinker can really question the established views that constitute the wall of expert scientific opinion that surrounds him or her and have a rational opinion that differs from the accepted view.” (Walton, 1997, pg. 2)

Appeals to authority are often seen in advertising; advertising companies believe, because it has been proven to be true, that people are likely to trust any figure of authority without knowing whether they are an expert in the field they are speaking on or not (Doos, n.d.). In an experiment known as “power decreases trust in social exchange”, it was discovered that individuals of lower power have an increased chance of trusting individuals of higher power, or figures of authority (Schilke, 2015). Furthermore, a series of tests performed by Solomon Asch proved that an individual is likely to follow the social norm; when asked a question, the individuals were found to answer with the majority rather than against it, for the most part, even if the majority was incorrect. (Asch, 2004) So, individuals are likely to trust appeals to authority, and that leads to a majority of people agreeing on a topic, making even more people likely to agree on it. Appeals to authority are also often seen in debates; in fact, some versions of competitive debate rely almost entirely on reading “cards” or quotes from purported authority. (Goodwin, 2011)

The appeal to authority fallacy is most easily explained through some of the many examples that have occurred throughout history. According to Gartler (2006), one of the most infamous examples is the fact that the scientific community regarded the number of human chromosomes to be 48 because the scientist who had broadcasted this number was well trusted by the community. Theophilius Painter was an established cytologist, and was well trained in this field, where he specialized in spermatogenesis. His work in cytogenetics brought him many honors, and he was considered to be one of the leading cytogeneticists of all time. In his study of human chromosomes, he broadcasted that there were 24 pairs of human chromosomes, with a total number of 48. Even he was unsure about this count, but in his paper that was published in 1923, he broadcasted this as the correct count of human chromosomes. The technique that he used to discover this number was poor; he had also examined testicular material from a Down syndrome case and reported nothing to be wrong with the chromosome count, which we now know to be wrong. This implies that Painter could not reliably detect an extra chromosome, which leads to the conclusion that his technique could not be relied on for counting chromosomes in general. However, his work in many other cases had been correct, and he was well trusted by the scientific community. So, while their technology was constantly be updated, scientists after him, even though several of them had leads that this number was incorrect, trusted his work. It was not until 1956, 33 years after Painter’s paper with the chromosome count was published, that this number was established to be incorrect. Two scientists, Joe Hin Tijo and Albert Levan, used modern techniques to determine the number of human chromosomes to be 46, with 23 pairs, and published this number in a paper. However, for 33 years, the number of human chromosomes was believed to be 48, because Painter, a figure of authority, had deemed this to be true. This is an example of appeal to authority which shows that authority is not right all of the time; while he could be trusted on many other conclusions, he was wrong about this, and due to his prestige people believed this count. With new technology and modern techniques, it is important that conclusions such as the human chromosome count are always being questioned and retested, because figures of authority are not right 100% of the time.

Another example is presented by a quote from Sylvia Browne, found in an article by Doos. “I predict we can truly say “goodbye” to the common cold in 2009 or 2010. The solution to the common cold involves heat. Keep in mind that the body’s first response when we develop a cold is to come down with a fever. Many doctors today no longer rush to push patients to take temperature-reducing medications when they come down with a fever, unless the fever is dangerous. They feel the immune system is the patient’s best medicine and should be given a chance to fight back. So as the immune system fights a cold with heat, the cure for the common cold certainly may lie in this first signal to heal.” Here, she is making a claim that there will be no such thing as the “common cold” is 2009 or 2010, and after that, because the body will use heat to destroy this. However, in 1988, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences report that there is no scientific justification from the research conducted over a period of 130 years for the existence of this parapsychological phenomena . They tested her hypothesis, and she was incorrect every time. Had one done research on Sylvia Browne, they would have discovered that her predictions could not be trusted, because her profession, which was a Psychic Detective and Clairvoyant, have never been substantiated as legitimate. So, her predictions, which she published for 2011, are an example of when authority cannot be trusted if their area of expertise is not legitimate.

A large area in which there is often appeal to authority fallacies is food and nutrition. Much of the food industry is devoted to advertising and promoting various foods and the basis of their argument is often that their foods are “healthy and nutritious” (Walton, 1997). As Walton expresses, (1997) often, to determine what we should eat, we go to our physicians, but their field of expertise does not qualify for them to be giving such advice, because the physician training does not specialize in this matter. The problem with this area is that there is not a specific field that can be deemed an expert, but rather several fields that play into the expertise. However, people are willing to accept the advice of physicians and other fields in terms of food; why this is cannot be proven, but it could be because often the advice that they give is harmless, and if they are wrong, there is no consequence. For example, if a doctor told you to eat more fruit, even if that doctor is not an expert in the field of nutrition, you may listen, because it is easy to eat more fruit and it cannot harm you to do so.

A more direct example of fallacy in terms of food and nutrition, also found in Walton, (1997), was at a lecture given by Nancy Appleton. Nancy Appleton had credentials that included a Ph.D. from the international University of National Education in Huntington Beach, CA. She gave a largely attended lecture in which she talked about the effect of sugar, and how it should never be consumed because it causes food allergies, diabetes, tooth decay, arthritis, heart disease and cancer. However, after the lecture, a critic claimed that the International University of Nutritional Education in Huntington Beach, CA, is a named that is used by a diploma mill, from where is also got a diploma for his dog and cat. So, this case proves that in order to trust someone who claims to be a figure of authority, and therefore to appeal to authority, one must be sure that his or her credentials are legitimate.

In terms of nutrition and diet, Dr. Mehmet Oz, celebrity from the Dr. Oz show, is another example of the expert opinion fallacy. Found in an article by NG (2014), Dr. Oz is a cardiac surgeon, and is in expert in that field. He is also famous, because he has his own show, “the Dr. Oz Show”, and is a friend of Oprah Winfrey. So, an audience, knowing that he is an expert in some field, trusts him and his opinion on many things. Often times, he is seen speaking about nutrition, and often promotes many weight-loss products. However, recently, he has gotten into trouble for falsely promoting a product that was proven not to work. He advocated that Green Coffee beans would help with weight loss, and is seen advertising products with this ingredient in them. Dr. Oz aired a show in May of 2012, which he promoted this product, and this publicity helped the manufacturer sell half a million bottles of these pills. A further article on this matter, (Burke, 2014), discusses how, after further research, it was discovered that the research recently done to prove that these pills helped with weight loss had illegitimate data. The results had been visibly altered to show that these pills helped with weight-loss, when in reality they did not. (Dr. Oz was grilled by the senate for the false promotion of these products, to which he responded, “My show is about hope”. While these pills may help with weight loss, there is no science behind them that proves this to be true, but Dr. Oz still promoted them as being “miracle pills”. (NG, 2014) The general public trusted what Dr. Oz said because he is a famous doctor, but he was not an expert in what he was promoting, and thus falsely promoted it.

Many times, celebrities are used to promote certain products, but those celebrities have absolutely no expertise in the given field. However, because they are figures of authority to the general public, they are trusted. An example of this occurred in a 1986 Vicks commercial, which promoted the use of adult Vicks. Peter Bergman, an actor from the television show “All My Children”, openly states, “I am not a doctor, but I play one of TV”, and then proceeds to promote medicine for adults (NG, 2014). Here, he is openly admitting that he is not a doctor and therefore cannot be trusted in terms of medicine, but still people bought Vick’s adult medicine.

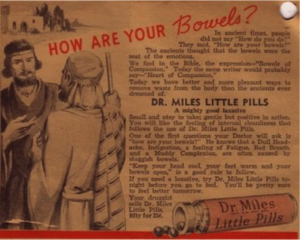

This is an advertisement for “Dr.Miles Little Pills”, which supposedly help with bowel movements. However, the advertiser appeals to the Bible as a figure of authority. Today’s healthcare is far more effective than it was in the time that the Bible was written, proven by the fact that our current life expectancy is much greater than it was in biblical times. (Doos, n.d.) So, the Bible is outdated in terms of healthcare, and it cannot be trusted as a figure of authority or as an expert in terms of this field, yet it is often used because people are inclined to trust the Bible for is expertise in other fields.

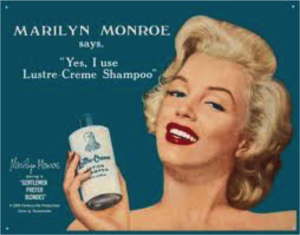

Here, Marilyn Monroe is used to sell Lustre-Cream Shampoo. While famous, and therefore trusted in terms of beauty by the general public , Monroe is by no means an expert in hair. However, she is appealed to as an expert in this field, because she is used to promote the legitimacy of this product. This is an example of when celebrities are paid to promote certain products, and when this is true, one cannot trust their opinion. This is seen many times in advertising, because the general public tends to trust familiar faces, such as celebrities, more than unfamiliar faces, which is logically inaccurate.

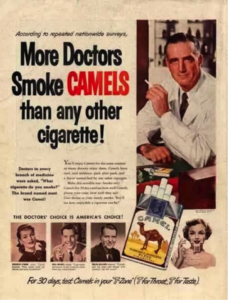

This is an advertisement for Camel cigarettes, promoting that “more doctors smoke camels than any other cigarette”. Pictured is a man who looks how one would expect a doctor to look, smoking a cigarette. This advertisement appeals to doctors, but it is vague; first of all, it does not clarify which doctors, but rather just a general “doctors”. Second, ones cigarette choice has nothing to do with their field of expertise; a doctor may be an expert in some subject, but that does not mean that they have the correct opinion about cigarette preference.

Similar to the advertisement above, this ad is promoting cigarettes. More specifically, this advertisement uses dentists to promote the product. However, while they use a dentist, there is not a specific dentist that they use, but rather “your dentist”, a claim that could be completely illegitimate. Second, similar to the advertisement above, being a dentist has nothing to do with cigarette preference; the opinion of “your dentist” on what type of cigarette to smoke is as legitimate as the opinion of anyone else that you ask.

All of these examples are fallacious appeals to authority. However, it is important to understand that not all appeals to authority are fallacious; if the authority that is appealed to is an expert in the subject field that is being argued, they can be trusted. Since so much of our information comes from experts, it is impossible to never believe one. Nevertheless, it is important to also remember that figures of authority are not perfect, and therefore may even be wrong within their field of expertise. But, for the most part, they can be trusted with information that is within their field of expertise. However, when appealing to authority, one should always ask these questions to begin: (Doos, n.d.)

- Is this a matter that I can decide without appeal to expert opinion?

- If the answer here is yes, one should always do so. It is much better to come to a conclusion without the help of an expert opinion, whether through the observation of a fact or another way, then to rely on the opinion of someone else.

- Is this a matter upon which expert opinion is available?

- If there is no expert opinion in a given matter, your opinion will be as good as anyone else’s. It is important to remember that an expert opinion should only be used if their opinion is more legitimate than yours.

- Is the authority an expert on the matter?

- This is the most important question to ask. If the authority is not an expert in the subject field that you are seeking an answer, then your opinion is as legitimate as theirs.

- Is the authority biased towards one side?

- If so, the authority may be untrustworthy. This could be hard to identify; in order to be unbiased, the figure of authority has to be completely disinterested from the subject field. That is, they do not want the results to go one-way or the other. A way to avoid this problem is to seek multiple expert opinions. This question could also be asked, as “is there sufficient agreement among the other experts in the subject”? It is important to make sure that there are multiple experts in a given field that have agreed on this subject.

Furthermore, these questions cold also be used to directly assess the expert’s credibility: (Goodwin, 2011)

- Expertise question: How credible is E[xpert] as an expert source?

- Field question: Is E an expert in the field that A[ssertion] is in?

- Opinion question: What did E assert that implies A?

- Trustworthiness question: Is E personally reliable as a source?

- Consistency question: Is A consistent with what other experts assert?

- Backup evidence question: Is [E]’s assertion based on evidence?

These questions should always be considered when an appeal to authority is made. The two sources that they come from both compliment, and add more detail to each other. The questions presented by Doos give a more general basis for ones decision, and the questions presented by Goodwin offer more detail about the expert themselves. Both are important to consider, and therefore compliment each other. If any one of these questions can be answered differently from what is expected if the figure of authority is trustworthy, then the appeal is obviously fallacious. In a more general sense, one should be aware that experts are not always right, and when making or believing an appeal to authority, assure that the subject in question is under the expertise field of the given figure of authority.

References

Asch, S. (2004). Opinions and Social Pressure. In E. Aronson, The Social Animal (pp. 17-27). Worth Publisher.

Burke, Lauren. (2014, October 21). Dr.Oz-Endorsed diet pill study was bogus, researchers admit. CBS News .

Doos, A. W. (n.d.). Appeal to Authority. Retrieved October 2015, from Appeal to Authority: www.appealtoauthority.info

Goodwin, J. (2011). Accounting for the force of appeal to authority. Iowa State University. OSSA Conference Archive.

Goodwin, J. (1998). Forms of Authority and the Real Ad Verecundiam. Northwestern University, Communication Studies. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

NG, N. (2014, June 21). Mehmet Oz: Example of Appeal to Authority Fallacy.

Oliver Schilke, M. R. (2015, August 26). Power decreases trust in social exchange. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the US .

S.M.Gartler. (2006). The Chromosome Number in humans: A brief history. Nature Reviews , 7, 1-6.

Walton, D. (1999). Appeal to Expert Opinion. Penn State Press.

IMAGE SOURCES

http://greencoffeebeanextractmax.net/

https://3e6643fe-a-62cb3a1a-s-sites.googlegroups.com/site/appealtoauthority/home/media-examples/Appealtoauthority-bowelbible.jpg?attachauth=ANoY7cohV0CHd_06LCYMYyKuun5hEKzhyWy2v4taFDAhNqVE__8g33vzu1J9UamuA8rQ7B110nya0NeVsyqjkd_9uKgbw7iNsAYrhPV_Dk7RVxosE–Ld1J9B7eWLayoLhYszodVJHNLQmG_SCMF_OPIegUEfxTzJlRZfawhTkR6Omr3VjbaUO76r6D10Aa9C4XiUFQ7lJJiQsWAcksxMrQfff4gBrfFtqpMKu_vaYzNLWvV5uQ4EC8Dd5wCltgVU7TZSlMyOGd2Oh4qyBj6A8WyA9qIFUSv6w%3D%3D&attredirects=0

http://www.amazon.com/Marilyn-Monroe-Lustre-Shampoo-Vintage/dp/B0012Q7KEA

https://3e6643fe-a-62cb3a1a-s-sites.googlegroups.com/site/appealtoauthority/home/media-examples/Appealtoauthority-doctorsmoke.jpg?attachauth=ANoY7coRJ4K_KKA2ahnj1sWjRVbzmtXZ3mFbg3aWijwlCI_nIcKWekmBmMT4ubrlJBGLKdDSZICOm_NjAEHTAJZWHuAVq76fEetsoUoSvtE8TGwoLJ9FwZe0DHNglAwjFSQayUafVFeDB9dwaEslwjoLUbjkqHjFx3oeaHZBAu9a7lV9zDayL2EsJiE7QyNNWn8ISmX-JS_tv65CsAEgvDH3TqP0h2JUN8d2Qnt8hCC6NbgrQN1svoRyYCI8iftNLHJ2FzHUmYmvfXv4aDdsSmu6Nt2Fkk-8iw%3D%3D&attredirects=0

http://www.appealtoauthority.info/home/media-examples