For years the media has led the public to believe many erroneous notions regarding science through its endless streams of faulty publications. Those misconceptions, in turn, have discredited science in its entirety and inspired a culture of doubt and distrust among the scientific community and the public. One of the most popular misconceptions about science is the notion of “scientific proof.” Although it may seem paradoxical, there is no such thing as “proof” in science, only scientific evidence. In order to establish the difference between the two concepts, it is important to understand what makes science a science? Contrary to popular belief, it is not the idea that it provides ironclad, irrefutable, final proofs for the many phenomena in our natural world. However, science is predicated on the ideas of observation, touch and replication. In other words, what is seen, heard, touched and replicated is the source of scientific knowledge. Nevertheless even if an experiment can be replicated, it does not necessarily “prove” anything; it only serves as evidence to support a theory. According to Kanazawa (2008), unlike mathematics, “All scientific knowledge is tentative and provisional, and nothing is final.”

Today, many of the misconceptions about scientific evidence stem from the idea that science and mathematics are one in the same in that they yield final results. It is important to note that mathematics is not a science. Although math is often used in science, it is merely a “language used by science” not a science in itself (Stewart, 2015). Mathematicians operate within an entirely different framework than that of science; the world of mathematics has already been defined. Moreover, the reason that mathematics provides definite and final proofs is because all elements of that field have been defined by the mathematicians themselves. Dr. David Stewart (2015) proposes that mathematics be thought of as a game where the rules and guidelines have already been set by an arbitrary person. Once the rules change so does the game. Consequently, “When you prove a mathematical theorem you are merely playing the game as defined by the system of mathematics in which you are engaged” (Stewart, 2015). For instance: the Pythagorean Theorem, a theorem regarding the lengths of a right triangle, has been proven and therefore is final. Even if the moon were to crash on earth, the proof will never change, because mathematics is not experimental. Science on the other hand is. The parameters of science have yet to be defined; today a scientist may provide evidence that support a theory; however, tomorrow another might introduce a better one. Therein lies the reasons why scientist use the term scientific evidence instead of “proof.”

Figure 1. Natural selection on the Galapagos. (Dailymail)

The data collected during scientific experiments either verifies or disproves a theory. Darwin’s experiment in the Galapagos Islands is an example. Darwin supported his theory of natural selection which later influenced his theory of evolution by observing specific characteristics and physical traits of boobies such as their beak size and shape in different regions of the Galapagos. He noticed that boobies with certain beak sizes and shapes were better suited for their respective environment because they could survive it. He also remarked that different beaks determined different food sources. Darwin formulated a theory, designed an experiment, in this case observing boobies in their natural habitat, and collected data that support his theory. Even though he found the necessary evidence, his theory still remains a theory. If it were a final proof or an irrefutable truth, there would not be so many controversies and competing evidence that work to disprove it. Creationists have argued that the theory of Evolution is incorrect or has many holes, because evolution is merely a theory; however, according to Kanazawa (2008) “what they [Creationists] neglect to mention is that everything in science is just a theory and is never proven.” That is the way science works; scientific evidence also known as Empirical evidence is founded on the empirical approach which posits that scientific knowledge and information are acquired through observation and experimentation (McLeod, 2008). First, scientists form their hypotheses then they design an experiment to support or disprove their theory (Bradford, 2015). The empirical process became the scientific approach in the 17th and 18th century as it influenced the development of many natural sciences including biology as evidenced by Darwin’s contribution (McLeod, 2008).

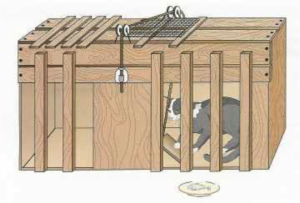

Even though scientific evidence is accepted in the scientific community to explain sciences such as biology and physics, many scientists do not believe that scientific evidence can be found in psychology. Furthermore, because psychology observes subjective concepts, it is considered a “soft science” that cannot be replicated. Apparently Thorndike’s law of effect (any behavior that is followed by pleasant consequences is likely to be repeated, and any behavior followed by unpleasant consequences is not likely to be repeated) is somehow less credible than Newton’s law of gravity. However, that it is not true, greater development in psychology proves that psychologists do employ the empirical approach. For instance, Thorndike devised an experiment in which he placed a cat in a puzzle box and recorded how long it would take the cat to find the lever to escape the box. After many trials, the cat took less time to open the box. This experiment suggested that the cat would press the lever more quickly because “pressing the lever would have favorable consequences” (McLeod, 2007). This experiment not only supports Thorndike’s law of effect but it can also be replicated. Therefore, scientific evidence does apply to psychology. Perhaps psychology is not as “soft” of a science as many have made it to be. However, it is important to note that not all experiments in psychology are relatively straightforward as Thorndike’s experiment; many experiments in that field have yet to be replicated (Belluz, 2015).

Figure 2. Cat in puzzle box. (CSUS)

The ultimate goal of science is to provide scientific evidence and data that have not been corrupted by biases. Because all humans are liable to err, empirical data is gathered by multiple scientists to ensure the objectivity of the data collected (Bradford, 2015). Consequently, you have to be careful when reading through the many fraudulent publications found in the media . A good rule thumb when researching is to look up information from varied reputable sources. This would help select the information and data that has been scientifically evidenced or supported from the questionable ones. This chapter was written using information from many trusted scientific sources. This method would also help avoid articles that are a product of p’hacking, the idea of reputedly testing a hypothesis to yield a positive result. It is dishonest, irresponsible and threatens the credibility of science (Michel, 2015). It also creates biases in a field that thrives on objectivity. Stay away from articles that claim certain information has been “scientifically proven,” because there is no proof in science. If you ever come across a scientist who claims that he has “proven” a phenomenon, he most likely did not. Certain titles such as “Chocolate Has been Scientifically Proven to help lose weight ,” “Scientists Prove that Eating Kale is Deadly,” or “ Scientific Proof Proves that the Moon Is Made of Sand” should serves as red flag that indicate unreliable information. The great physicist Richard Feynman once said, “I have approximate answers and possible beliefs in different degrees of certainty about different things, but I’m not absolutely sure of anything.” Scientific proof does not exist in science; however, mathematics does satisfy the need for absolute and final proofs.

References

Belluz, Julia. (2015, August 27). Scientists Replicated 100 Recent Psychology Experiments. More Than Half of Them Failed. Retrieved October 29, 2015, from http://www.vox.com/ 2015/8/27/9216383/irreproducibility-research

Bradford, Alina. (2015, March 24). Empirical Evidence: A Definition. Retrieved October 29, 2015, from http://www.livescience.com/21456-empirical-evidence-a-definition.html

Kanazawa, Satoshi. (2008, November 16). Common Misconceptions about Science l: “Scientific Proof.” Retrieved October 29, 2015, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-scientific- fundamentalist/200811/common-misconceptions-about-science-i-scientific-proof

Lewis, Geraint. (2014, September 23). Retrieved October 29, 2015, from

http://theconversation.com/wheres-the-proof-in-science-there-is-none-30570

McLeod, Saul. (2008). Psychology as a Science. Retrieved October 29, 2015, from

http:// www.simplypsychology.org/science-psychology.html

Michel, Matt J. (2015, August 13). 6 Reasons You can’t trust Science Anymore. Retrieved October 29, 2015, from http://www.cracked.com/article_22712_6-ways-modern-science-has-turned-into-giant-scam.html

Morrison, Sarah. (2011, October 22). Booby that Inspired Darwin Caught in an Evolutionary Trap. Retrieved October 29, 2015, from http://www.independent.co.uk/environment/nature/booby-that-inspired-darwin-caught-in-an-evolutionary-trap-2298607.html

Stewart, David. (2015). Mathematical Proof vs. Scientific Proof: Are They the Same? Retrieved October 29, 2015, from http://healthimpactnews.com/2014/mathematical-proof-vs-scientific-proof-are-they-the-same/