Reading an Interlinear Analysis

Caroline Gihlstorf

This module is an introduction to a type of linguistic analysis you might come across when reading about a Zapotec text or manuscript. The chapter walks you through the analysis of the first line of a manuscript written in Colonial Valley Zapotec to give you an idea of how these analyses generally work. There are a lot of little details scattered throughout this chapter — but don’t worry! This chapter assumes little to no linguistic knowledge, and you don’t have to understand everything to get something out of it.

Resources in this module: Abbreviation Chart · Teaching Summary · Answer Key

1. Introduction

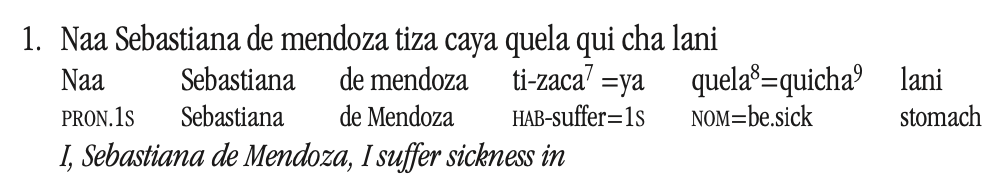

How do linguists show what a sentence in a particular language means to those who don’t know that language? Oftentimes, they construct something like this:

This way of organizing and marking up sentences is called an interlinear analysis. Interlinear analyses represent a sentence or phrase on multiple levels to show what each word means and how all the parts fit together. People have different ways of learning words in a new language. Interlinear analyses are just one way linguists communicate what they know about the language they’re studying.

It’s likely that you haven’t seen an interlinear analysis before — that’s okay! Looking at an interlinear analysis for the first time and trying to navigate all the pieces and parts can be intimidating, but don’t let that discourage you. You have the ability to learn and understand interlinear analyses, and this chapter was designed assuming that everything we will cover is new to you. You can do it!

Interlinear analyses focus on understanding the meaning of morphemes. Morphemes are pieces of words that hold meaning, but which cannot be broken down into smaller meaningful segments. Undo, for example, is a word that can be broken into two parts: un- and do. There are no smaller components that either un- or do can be broken down into that make any sense (u, n, d, and o have no meaning on their own). Un- and do are thus morphemes. Although you do not need to know the finer details of morphemes to get through this chapter, you can find information that delves deeper into the properties of morphemes in this guide from the Rochester Institute of Technology (n.d.) or this video by Crash Course (2020).

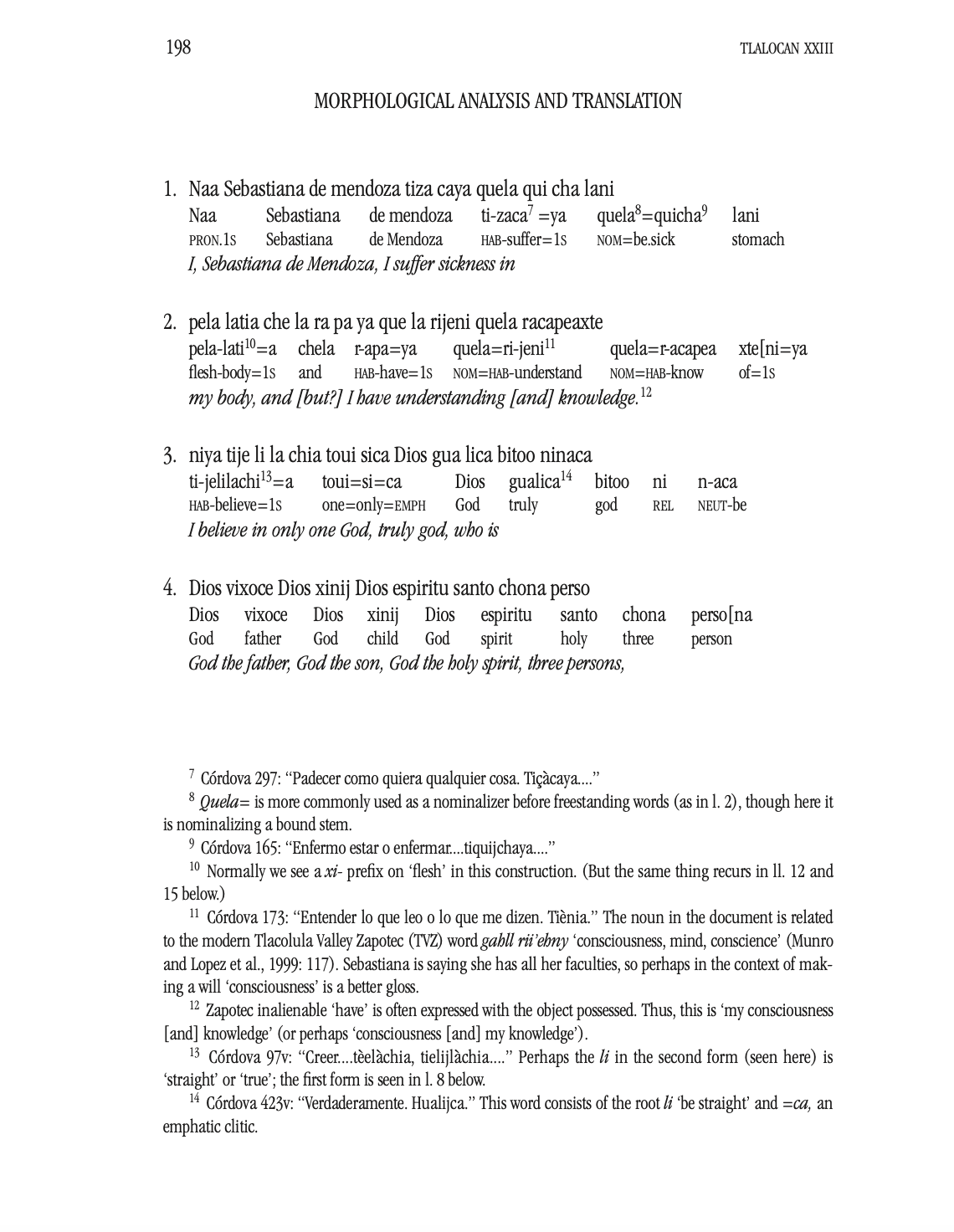

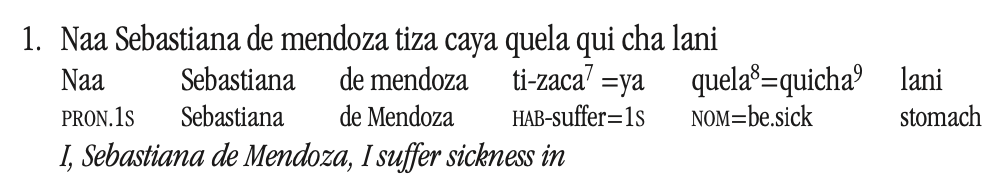

How is an interlinear analysis structured? Interlinear analyses consist of several lines of text, the first being the original sentence or phrase in the language. Each following line gives different details about the sentence, and presents a unique way of interpreting it. As an example, consider the following interlinear analysis of the first ten words of the Zapotec language testament of Sebastiana de Mendoza, as published in Munro et al. 2018 (you are welcome to look at the entire document as you move through this chapter).

This interlinear analysis has four lines, each of which serves a different purpose. Line 1 is a faithful transcription of the original manuscript (you can compare it with the original manuscript on Ticha). Line 2 groups parts of the original transcription into morphemes for linguists to identify and analyze. Line 3 lists the direct translation or linguistic category of the morphemes in line 2. Line 4 gives a translation of the phrase in line 1 that makes sense in English when read in its entirety. Below are more in-depth descriptions of each of these lines.

2. Line by line guide

Line 1

The first line is a transcription of the handwritten sentence in Colonial Valley Zapotec, keeping as close as possible to the spacing, and punctuation in the original manuscript.

Lines 2 and 3

Line 2 presents a breakdown of morphemes that linguists want to focus on. The goal of this breakdown is to show what the linguists doing the analysis interpret as words, and which morphemes they see composing those words. Clearly distinguishing each morpheme makes it easy for linguists to attribute meanings to them later on, in particular in line 3.

Lines 2 and 3 use special symbols to show how morphemes are being combined. These symbols can differ among analyses, depending on the linguist. In this analysis, morphemes are separated by dashes (“-”) and equal signs (“=”). In Figure 2, ti and zaca are each morphemes, separated by a dash. Another relationship we see is quela=quicha, denoted by an equal sign. Quela and quicha are both parts of a larger word conveying the meaning of ‘sickness’.

What distinguishes the morphemes separated by dashes from the morphemes separated by equal signs? The difference is in how the morphemes are connected to other morphemes or words, and can be thought of as being either tightly connected or loosely connected. The morphemes separated by dashes are called affixes, which are tightly connected to other words or morphemes. The equal signs separates morphemes called clitics, which are loosely connected to other words or morphemes. If you’re familiar with Spanish, consider the phrase ayudame – ‘help me’. Ayudame contains the affix ‘a’ and the clitic ‘me’: ayud–a=me. ‘a’ is tightly connected, while ‘me’ is loosely connected.

Why are there spaces between morphemes in line 1 that aren’t present in line 2 (qui cha versus quicha, for example)? One reason that these spaces likely exist is due to differences in how scribes interpreted where words began and ended. Line 2 is where linguists may change spacing to identify morphemes for their analysis. English contains words like these, too. These are words that contain smaller words within them — dog house being one example. Some people believe they should be combined using a hyphen (dog-house), others prefer using a space between the words (dog house) and some may even think the two words should be combined to create a single, larger word (doghouse). Colonial Zapotec scribes may have also had different ways of conceptualizing how parts of words fit together, depending on what looked best to them. Practical limitations such as running out of ink or space on the page could have also resulted in different spellings and spacings than we would expect to see today.

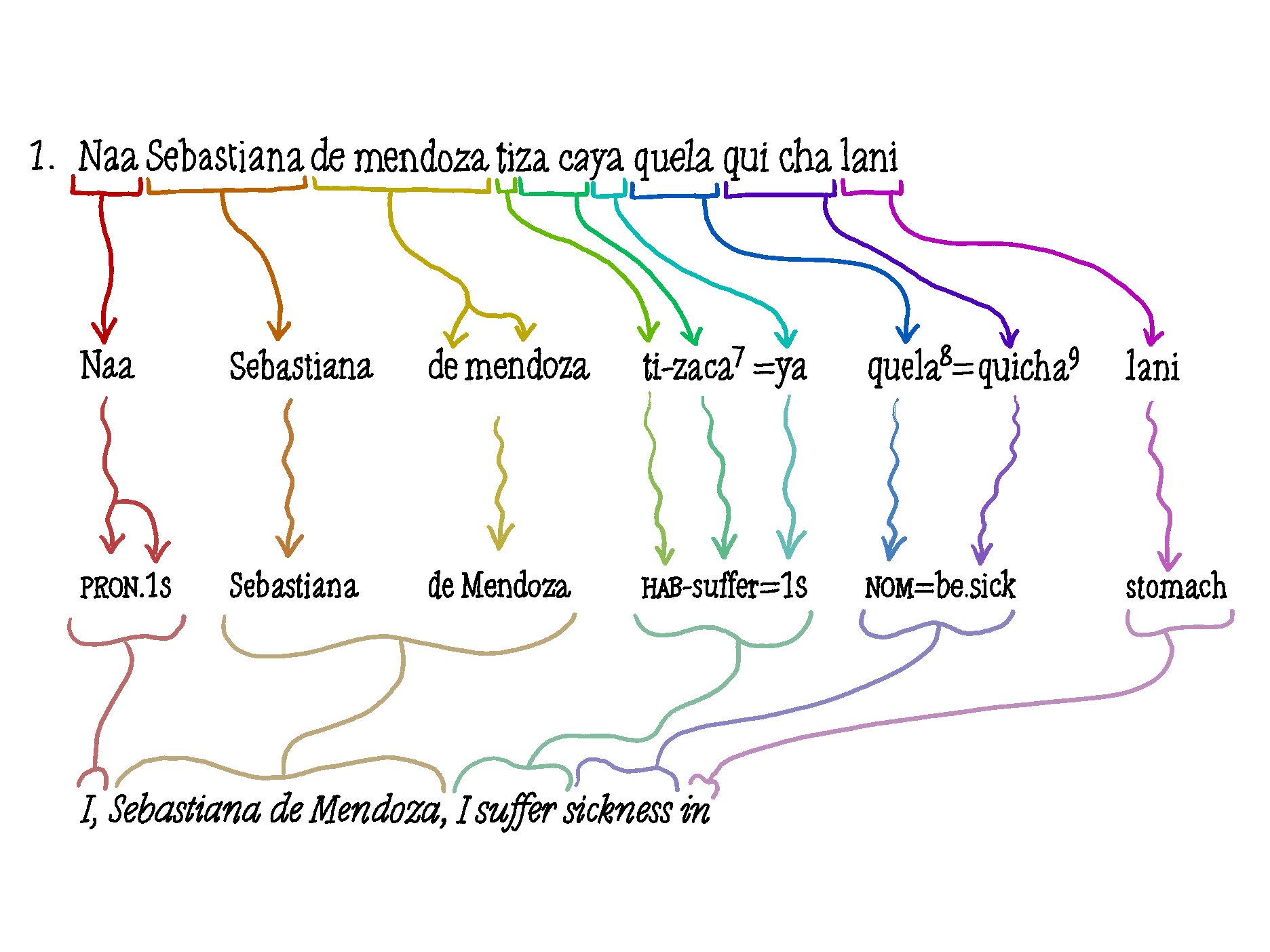

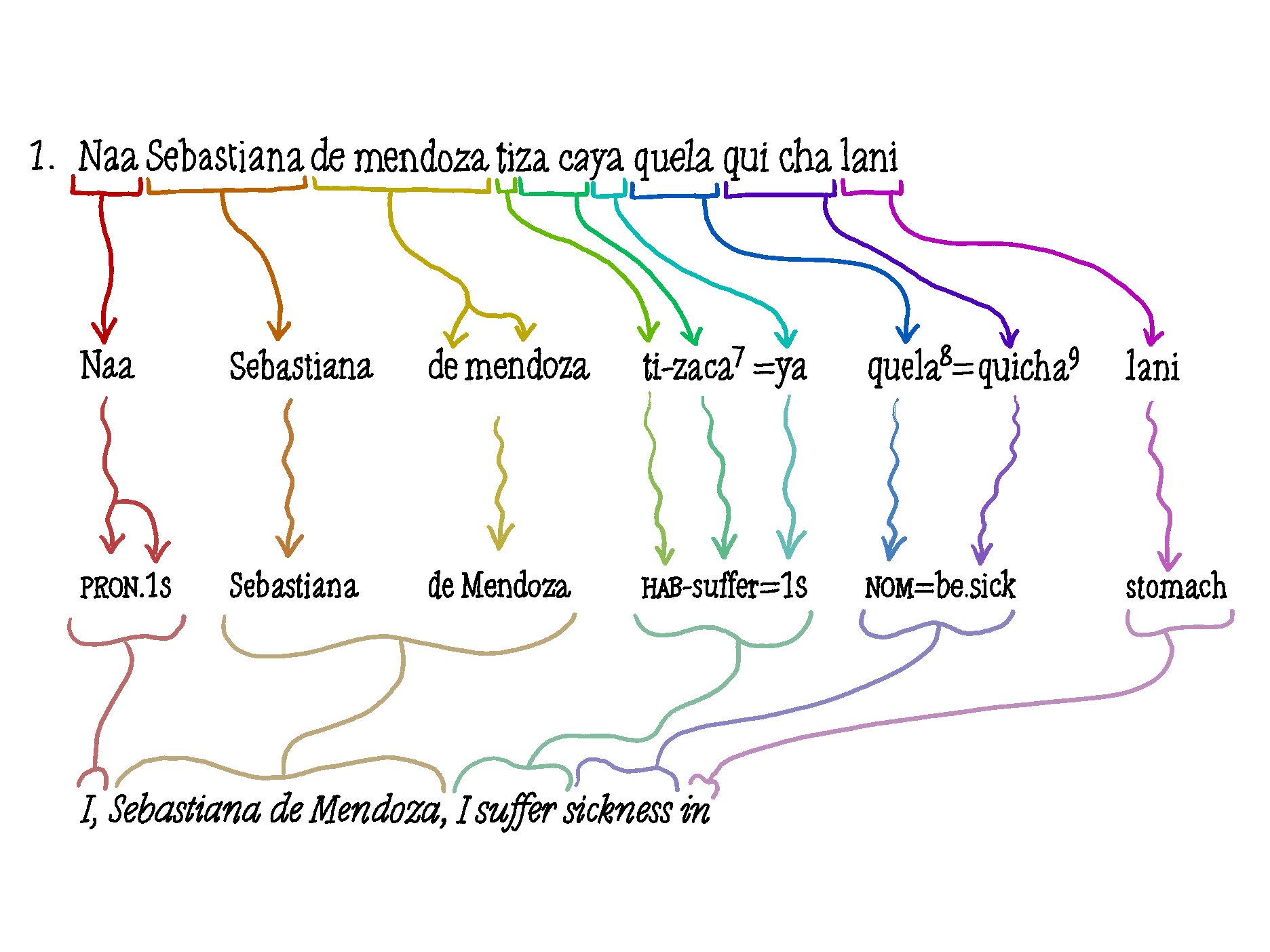

Below is a visual illustration of how the different words and labels in an interlinear analysis connect with one another from line to line:

You may have noticed the superscripts above some of the words in line 2. These correspond to footnotes in the paper from which this analysis was taken. These footnotes give us additional information from the linguists who wrote the analysis. You may find the information interesting or helpful to you, but it is also okay to skip the footnotes and just focus on the main text. The information you’ll find in the footnotes includes historical context to words, references to the colonial dictionary for words that support the linguists’ analyses, and things that linguists aren’t sure about.

You may have also noticed some similarities between lines 2 and 3. Though similar to line 2, line 3 has a slightly different purpose. Also known as the gloss, line 3 lists a short translation of each morpheme in line 2, in the order in which they appeared in the phrase. Glosses stay true to the original Zapotec, regardless of whether they would make sense when uttered in English. This allows the reader to map each Colonial Valley Zapotec word to a direct translation while maintaining the original order of words in the sentence. The gloss is helpful because it allows readers to see each part of a Colonial Valley Zapotec word along with its translation.

Look at the last word of the second line — lani. Line 3 tells us that lani is glossed as ‘stomach’ in English. The rest of the words in line 3 are also glosses of the words above them. Another example we see towards the beginning of the line is that Sebastiana de mendoza is glossed as ‘Sebastiana de Mendoza’. This makes sense — the person’s name is their name.

Looking at the other glossed morphemes given in line 3, we see that many of them contain odd-looking labels with, or in place of, English words. One such label is “PRON.1s” underneath the word Naa. Linguists use abbreviations to represent some common abstract meanings like “first person pronoun” and “past tense”. These are often very technical categories often of great interest to linguists — don’t worry if you don’t understand all of these abbreviations and categories. The abbreviations will be explained in more detail later in the chapter.

Line 4

The fourth and final line of this interlinear analysis is a full translation of the original sentence or phrase (here, into English).

This translation is useful because although glosses of each Colonial Valley Zapotec word are listed in line 3, their order may seem odd to English speakers because English orders its words differently than Colonial Valley Zapotec does. Translations try to replicate the original sentence’s structure and meaning as much as possible; they sometimes have to be re-interpreted in order to make the most sense. Translating the sentence in line 1 word-for-word, for example, could result in something like “I, Sebastiana de Mendoza suffer I ness-sick stomach.” The ‘ness’ in this translation comes from the abbreviation “NOM” under the morpheme quela. “NOM” is an abbreviation of the word nominalizer. This label tells us that the morpheme quela= transforms the verb quicha — ‘be sick’ — into the noun ‘sickness’.

Another important thing to note is that lani is interpreted in line 4 as the preposition ‘in’, even though it is glossed as the noun ‘stomach’ in line 3. Can you see why this might be the case?

This word-for-word translation sounds awkward in English and loses many of the connotations it carries in Colonial Valley Zapotec. Line 4 interprets how any English speaker might convey the same ideas in a way that more naturally fits their language.

Exercise 2.1

Part I: Look at the translation of the Colonial Valley Zapotec text given in the fourth line. Given the glosses, what are some other ways you could translate the words?

Part II: What sounds most natural to you? What do you notice about these different translations?

3. Abbreviations

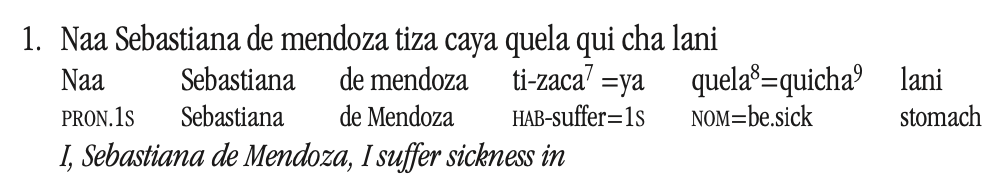

Take another look at the interlinear analysis of the first ten words of the Sebastiana de Mendoza text, this time focusing on the labels that appear under certain words in the third line:

There are three abbreviation that occur in this particular analysis: PRON.1s, HAB, and NOM. We read above that NOM is short for “nominalizer”.

Exercise 3.1

Try to guess what the other two abbreviations (PRON.1S under naa, HAB under ti-, and 1S under =ya) might mean before reading the rest of this explanation.

- The label 1S refers to the “first-person singular”, which is used when a person is referring to themselves, as in the English words I and me. (If you’re interested in why Naa is represented by the abbreviation PRON.1S while =ya is represented only by ‘1S’, this is because Naa is a free morpheme while =ya is a bound morpheme. You don’t need to know this to get through the chapter, however.)

- The HAB label shows that the morpheme ti- indicates a habitual action — an action that occurs regularly, or which is constant over a particular period of time.

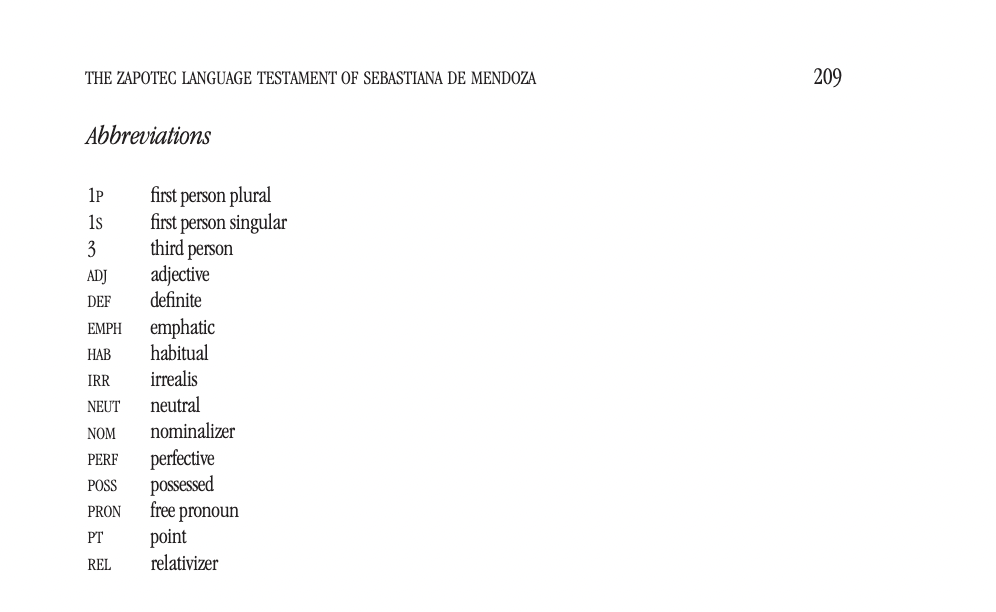

This way of labeling morphemes helps in understanding the sentence structure of Colonial Valley Zapotec and how meaning in Colonial Valley Zapotec is formed by specific combinations of morphemes. To view the definitions of these abbreviations in more detail and explore the meanings of other abbreviations present in the Sebastiana de Mendoza text, you can consult the table of abbreviations and their definitions available in this book.

While we created this list of abbreviations for this chapter, most papers that use interlinear analyses should have their own list of abbreviations (or an explanation of the abbreviations they’re using), since linguists make different choices about what to call certain categories and how to abbreviate them. The list of abbreviations is not always found in the same place — common places to find this list are at the beginning of a text, at the end of text, in the first footnote, or in an appendix. In the Sebastiana de Mendoza text, the authors explain the abbreviations they use on the page right before the actual text is presented, as you can see below.

If the information about abbreviations provided to you by the paper you’re reading is hard to understand, not very informative, or absent altogether, don’t worry — you’ll still be able to get something out of reading it even if you don’t understand every single thing. You may be able to find some answers through a Google search, though the definitions of some terms may be very complicated. Don’t be too discouraged if you don’t understand them right away.

Exercise 3.2

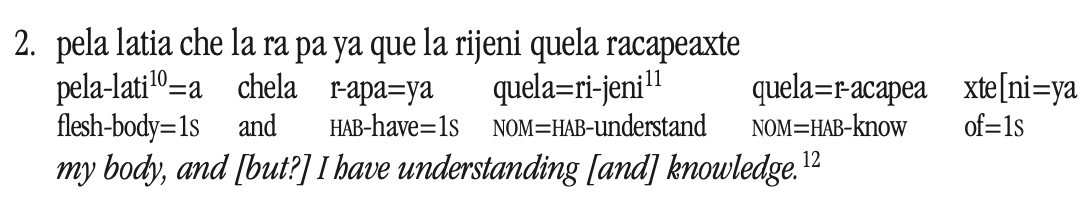

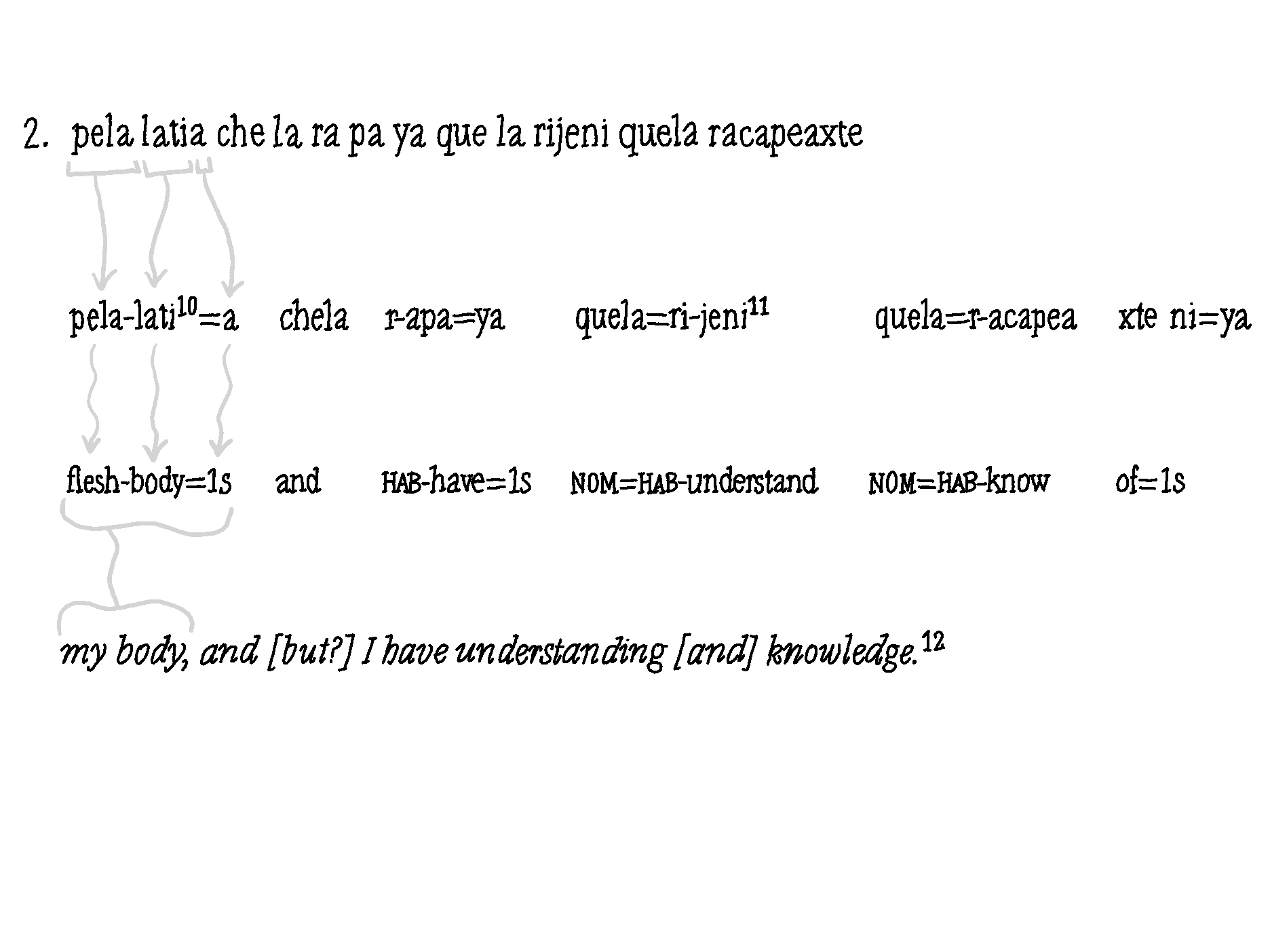

Below is an interlinear analysis of the next set of words from the Sebastiana de Mendoza text:

Explore the abbreviations you see in the third line of the analysis by answering the following questions: What do each of the labels tell you about the particular morpheme they are referring to? How does this meaning fit into the larger word and how it could be interpreted/translated? Consult the table of abbreviations as needed.

4. Additional exercises

One final note: the interlinear analysis of the Sebastiana de Mendoza text used in this chapter represents one of many ways to structure and assign notation for these kinds of analyses. Some linguists use analyses with three or five lines, and some use different notations to denote things like morpheme boundaries (i.e., different symbols than “=” or “-” from the examples we looked at). But regardless of a linguist’s particular way of writing things, what you learned in this chapter should help you identify familiar patterns and structures of any future interlinear analyses you come across. Don’t be nervous — this is something that everybody, linguist or not, has the ability to learn and understand.

Exercise 4.1 How does it work in your language?

Select three lines from the interlinear analysis of the Sebastiana de Mendoza text. Look closely at the transcription and interlinear analysis. Do you recognize any words?

Exercise 4.2

Using the illustration of line 1 as a model, draw arrows that connect morphemes, the glosses of those morphemes, and corresponding English translations for line 2. The first few morphemes are done for you.

Exercise 4.3

Exercise 4.4

Try taking a sentence or phrase from your language and glossing it into English (or Spanish, or another language you know). What do you notice? What kinds of decisions did you have to make?

Exercise 4.5 How does it work in your language?

Try translating one of the lines from the Sebastiana de Mendoza text into your language. In what ways is your Zapotec language similar to the Zapotec in Sebastiana de Mendoza’s will? In what ways is it different?

References

CrashCourse. 2020, Sept 18. Morphology: Crash Course Linguistics #2 [Video]. YouTube. www.youtube.com/watch?v=93sK4jTGrss

Munro, Pamela, Kevin Terraciano, Michael Galant, Brook Danielle Lillehaugen, Xóchitl Flores-Marcial, Maria Ornelas, Aaron Huey Sonnenschein, and Lisa Sousa. 2018. The Zapotec language testament of Sebastiana de Mendoza, c. 1675. Tlalocan XXIII: 187-211. https://revistas-filologicas.unam.mx/tlalocan/index.php/tl/article/view/480/458

Rochester Institute of Technology. (n.d.). What are morphemes? SEA – Supporting English Acquisition. https://www.rit.edu/ntid/sea/processes/wordknowledge/grammatical/whatare