Numbers

Brook Danielle Lillehaugen

This module is an introduction to the number system in Colonial Valley Zapotec, a form of Valley Zapotec attested in writing during the . This chapter could be a good place to start your study, though it might be helpful to complete Ticha or Colonial Documents and Archives first. After reading Numbers, you may find it useful to continue with Language Shift or Reclaiming our Languages.

Resources in this module: Teaching Summary · Answer Key · Spanish Version

1. Introduction

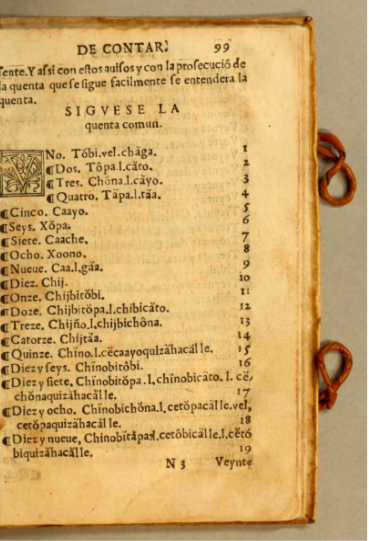

The text in the image below is from a grammar about Valley Zapotec which was published in 1578. The grammar is credited to a Spanish friar Juan de Cordova, though many unnamed Zapotec people contributed as well. The page in Figure 1 shows the Colonial Valley Zapotec words for the numbers 1-19.

Zapotec languages (there are many!) belong to the Otomanguean stock and are indigenous to what is now Oaxaca, Mexico. There are probably over 400,000 speakers of Zapotec languages today, and many Zapotec speakers are actively resisting linguistic and cultural threats from deeply embedded discriminatory beliefs and behaviors that deny and devalorize the Zapotec language, people, and knowledge.

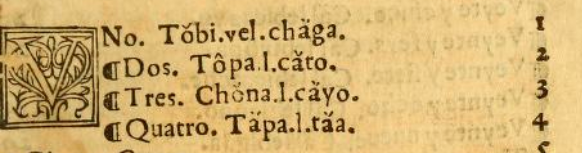

2. Learning to read Cordova: Numbers 1-4

Even though this book is printed, you might find it more challenging to read than modern printed books. Learning to read older printed books is a skill you can practice! Let’s take a look at Figure 2, which is a close up of the numbers 1-4.

Exercise 2.1

(b) Compare your transcription with a classmate’s.

Here’s my transcription:

VNo. Tǒbi. vel. chäga. 1

¶Dos. Tôpa. l. cǎto. 2

¶Tres. Chǒna. l. cäyo. 3

¶Quatro. Täpa. l. tǎa. 4

There’s lots of things to talk about even in these four lines! Let’s go back to just the first line:

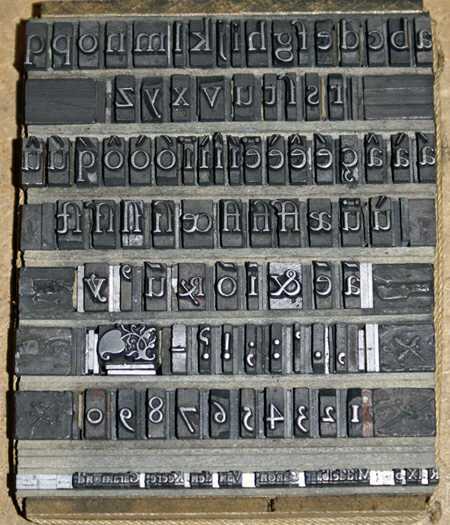

- The book was not printed digitally like today, but with metal casts of individual letters that could be arranged in lines to make a page. This technique is known as . An image of movable type can be found in Figure 3. (You may sometimes find a letter was placed upside down or a similarly shaped letter was substituted for an expected letter—it’s easy to imagine how this could happen!)

- V: The V is in the form of an ornate woodcut. Sometimes these can be quite elaborate and examples of other woodcuts can be seen in Figure 4. Figure 5 shows how these woodcuts would work—much like the moveable type! (The use of a <v> where we might expect a <u> nowadays is typical.)

- N: It might be surprising that the <N> is capital, and not lower case, as it is the second letter in the word. It seems the <V> wood-cut doesn’t “count” as the first letter, so the second letter was capitalized here as well.

- Notice the period after <VNo>. In fact there are lots of periods—more than we might expect. The period seems to be separating words here.

- ǒ: There is a caron (or hachek) over the <o> and you might be wondering what it means. Zapotec languages are tone languages, so we might wonder if this (and other ) are marking . However, our current best guess is that they are marking stress, that would mean that in this word the <to> syllable is the stressed one, i.e. the one that is a little louder and a little longer.

- vel: Vel is the Latin word for ‘or’. Note that we are only three words into this line and we already have encountered three languages: Spanish, Zapotec, and now Latin!

- ä: Again, you may be wondering about the diarisis (or umlaut) over the <a>. You already know that we think the caron is likely marking stress. It turns out we think that any diacritic (caron, circumflex, diarisis, acute, or grave accent) could mark stress. We are not sure if they were used to mean different things, or if the choice between which mark had more to do with which happened to be available to the typesetter.

Let’s look at the second line now—which will be much easier!

- ¶: The pilcrow (paragraph mark) seems to be acting like a bullet point.

- ô: You already know what we think this means- stress!

- l.: <l.> is an abbreviation for vel ‘or’.

While you might be surprised that it took nearly a page to explain two lines, look at how much easier this is to read now that you know a few simple things.

Exercise 2.2

Now that we’ve looked at the form, let’s turn to the content! Notice that there are two Zapotec words listed for each number. In fact, for the numbers one, two, three, and four only there are two sets of words, referred to here as Set A and Set B. Set A is the main set. Set B is an alternate set, used only when counting flat things, like tortillas.

Set A Set B

-

- tobi chaga

- topa cato

- chona cayo

- tapa taa

3. Putting together higher numbers

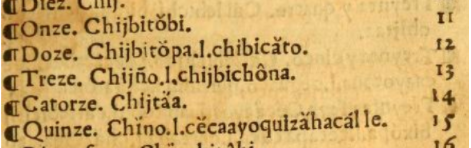

Let’s jump ahead now to some bigger numbers. Just like in languages that you already know, most higher numbers in Zapotec are composed of building blocks based on the lower numbers. Think about the English number fifteen which has two parts: the fif part which is related to ‘five’ and the teen part that is related to ‘ten’. In Zapotec, most higher numbers are also built from pieces related to words for small numbers, but maybe not in the same way that you’re used to! Let’s look now at Figure 6, a close up for the words for 11-15.

I’ve pulled out the Zapotec words and transcribed them below leaving out any accent marks for now. You may recognize tobi at the end of chijbitobi ‘11’ from above—it is the word for ‘1’. Chij is the word for ‘10’ and bi is a piece that can be used in bigger numbers to mean ‘and’ or ‘plus’, though it isn’t the regular word for ‘and’ in other contexts—it’s a special ‘and’ for numbers only. So ‘11’ in Zapotec is ‘ten and one’, which makes sense, of course! ‘12’ is ‘ten and two’ as shown below, though there are two different ways to say it—one uses the set A number for ‘2’ and one uses the set B number for ‘2’. We don’t have many examples, but we would expect that chijcato ‘12’ would be used to count flat things, since it has the B-set form for ‘2’ in it.

11. chij-bi-tobi

10-and-1 [=11]

12. chij-bi-topa

10-and-2 [=12]

or

12. chij-cato

10-2(B) [=12]

Let’s skip now to ‘15’. The first form for ‘15’ is chino. While this might look like it could start with the word for ‘10’, it doesn’t have anything that looks like ‘5’ in it. So we’ll say that this word on its own means ‘15’. There is another, longer way, to say ‘15’ as well, which seems to mean ‘another 5 will walk to 20’. What could that mean? In this case, it looks like 15 is being calculated based on its relationship to 20—that you’re 5 away from 20 and that if you go another 5 you’ll arrive at 20. That makes sense, too!

15. chino [=15]

or

15. cecaayo quizaha calle

ce-caayo qui-zaha calle

another-5 IRR-walk 20 [=15]

‘another 5 will walk to (arrive at) 20’

(You might notice that we’ve added a dash in the middle of ce-caayo to indicate that ce- means ‘another’ while caayo means ‘five’. You can learn more about this type of translation in the module Reading an Interlinear Analysis.)

4. Building blocks for numbers

You know almost everything you need to know to start doing some Zapotec math on your own! Here we listed all the parts you’ll find in the numbers 1-24,000, including the ‘and’ and ‘another’ in (a)–(b); the verb ‘will walk to’ that we just saw (c); and number roots 1–16,000. Use these as your reference to figure out the higher numbers in Exercise 4.1.

a) bi-[number] ‘and [number] more, plus [number]’ (like in 11)

b) ce-[number] ‘another [number] until’ (like in 15)

c) quizaha ‘will walk to’ (like in 15)

| Set A | Set B | |

| 1 | tobi | chaga |

| 2 | topa | cato |

| 3 | chona | cayo |

| 4 | tapa | taa |

| 5 | cayo | |

| 6 | xopa | |

| 7 | cache | |

| 8 | xono | |

| 9 | caa | |

| 10 | chij | |

| 13 | chijño | |

| 15 | chino | |

| 20 | calle, lalle | |

| 40 | toua | |

| 60 | cayona, quiyona | |

| 80 | taa | |

| 100 | cayoa, quioa | |

| 200 | chija | |

| 300 | chinoa | |

| 400 | ela | |

| 8,000 | çoti | |

| 16,000 | topa |

Exercise 4.1

Your turn! Each of the following numbers is already split into parts for you. Figure out the composition of each number, then explain how they mean what they mean.

16. chino-bi-tobi

17. chino-bi-topa

or chino-bi-cato

or ce-chona qui-zaha calle

18. chino-bi-chona

or ce-topa calle

or ce-topa qui-zaha calle

19. chino-bi-tapa

or ce-tobi calle

or ce-tobi qui-zaha calle

20. calle

21. calle-bi-tobi

22. calle-bi-topa

or calle-bi-cato

23. calle-bi-chona

or calle-bi-cayo

24. calle-bi-tapa

25. calle-bi-cayo

26. calle-bi-xopa

27. calle-bi-cache

28. calle-bi-xono

29. calle-bi-ga

30. calle-bi-chij

Exercise 4.2

Exercise 4.3

Ready for a challenge? In the numbers below you’ll notice that there are no hyphens that divide the words into their meaningful parts. This time, figure out what the parts are and analyze them as you did in Exercise 4.1. (While we stop here at 24,000, the Zapotec number system could be used to count higher, of course! There is no reason it couldn’t continue to count infinitely high.)

31. callebichijbitobi

32. callebichijbitopa

33. callebichijbichona

34. callebichijbitapa

35. callebichino

40. toua

41. touabitobi

50. touabichij

51. touabichijbitobi

60. cayona

100. Cayoa

120. Xopalalle

130. Xopalallebichij

140. Cachelalle

200. Chija

400. Tobiela

500. Tobiela cayoa

600. Tobiela chija

800. Topaela

1,000. Catoela chija

1,600. Tapaela

2,000. Cayoela

4,000. Chijela

8,000. Chagaçoti

or tobiçoti

24,000. Chonaçoti

Exercise 4.4

Explain how the phrase tapa ella chela cayona bixopa means ‘1666’. Some words may be spelled slightly differently than you saw above!

(This number appears in the first couple lines of a bill of sale written in San Miguel Etla in 1666. You can see the images here: https://ticha.haverford.edu/en/texts/SME666/.)

Exercise 4.5

Ready for a challenge? Based on the pattern you figured out in Exercises 4.1, 4.3, and 4.4, how do you think you would say the following numbers in Colonial Valley Zapotec?

74

86

97

124

136

402

5. Number systems and bases

Number systems in the world’s languages can use different bases. English uses a base-10, as numbers over 10 are built on 10 and powers of 10 are specially named: e.g. ten, hundred, thousand.

Exercise 5.1

Zapotec has a long history of writing and shares a system for representing numbers with other languages in the cultural area.

Exercise 5.2

6. Zapotec numbers today

Listen to the numbers in Zapotec as spoken today in San Jerónimo Tlacochahuaya, the same town where the grammar of Colonial Valley Zapotec (see Figure 1) was written nearly 500 years ago. Maestro Moisés García Guzmán has a playlist of the numbers 1-100 on his YouTube channel.

(For more on the differences between counting in Colonial Valley Zapotec and Modern Valley Zapotec, see the chapter on Language Shift.)

Exercise 6.1

Exercise 6.2 How does it work in your language?

What are the numbers like in your language? What similarities and differences do you notice between the numbers in your language and the numbers in Colonial Valley Zapotec?

Exercise 6.3

References

Blokland, Frank E. 2012. On the origin of Patterning in Movable Latin Type. https://www.lettermodel.org/

Cordova, Fray Juan de. 1578. Arte en lengua zapoteca. Mexico: En casa de Pedro Balli. Facsimile on archive.org, courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library. https://archive.org/details/arteenlenguazapo00juan

Heller, Steven. 2018. Initial Caps: The Birth of Illustrated Typography. Design Observer. https://designobserver.com/feature/initial-caps-the-birth-of-illustrated-typography/39885

The Mexican Colonial Period, the time between the colonization of the region by Spain and the independence of Mexico, stretches from 1521 to 1821.

Movable-type printing is a printing technology utilizing individual metallic cast letters that can be arranged one by one in lines to make a page to be printed. Like engravings, this page is the mirror image of the eventual print. Ink is applied to the page to be printed and then the entire page is "stamped" on paper. When reading documents printed with movable-type, it is not uncommon to notice letters that were placed upside down or similar shaped letters substituted for an intended letter.

A diacritic is a mark written above or below a letter, indicating a difference in pronunciation. You might recognize acute accents (á) from Spanish or diaereses/umlauts (ä) from German.

In some languages, the pitch or tone of a word affects the meaning. For example, in Teotitlán del Valle Zapotec, dyag with a low tone means 'ear', while dyǎg with a rising tone means 'hare'.

An affix is attached to a word to modify it's meaning. A prefix is attached to the beginning of a word, while a suffix is attached to the end. For example the English word unhappiness is composed of the prefix un-, the root or base word happy, and the suffix -ness.

Mesoamerica describes the geographic area between central Mexico and northern Costa Rica. Indigenous cultures of Mesoamerica speak many different languages, but have a long shared history of trade and cultural exchange.