Aside from being in day-to-day control of CTR, Watson was also directly responsible for Tabulating Machine. Hollerith’s outfit seemed to have the greatest growth potential, and Watson knew it. Although Tabulating Machine had only a handful of salesmen, it was swamped with orders – the market for its goods was practically limitless. At the same time, however, it suffered from several serious problems. Since it leased rather than sold its equipment, it had a steady and quite sizable annual income but a rather anemic cash flow, which inhibited its expansion. In addition, Hollerith’s patents were due to expire in a few years, and Tabulating Machine was facing its first competitor.

In 1905, after Hollerith had stubbornly refused to lower his rental fees, the Census had decided to develop its own tabulating equipment. It hired a Russian-born engineer named James Powers, who managed to develop a mechanical line of punchers, sorters, and tabulators that circumvented Hollerith’s patents. Much to old Hollerith’s shock and outrage, the Census proceeded to make its own machines for the 1910 head count, buying only the cards from Hollerith. After the census was completed, Powers established his own company. He developed an electric card puncher that outperformed Hollerith’s mechanical punchers and, even more threatening to Tabulating Machine, a tabulator that automatically printed out its results. Powers also undercut Tabulating Machine’s prices, selling as well as leasing his devices.

Although Powers’ outfit was much smaller and less established than Tabulating Machine, its existence forced CTR to become more competitive. Watson had no intention of switching to sales – leasing was too lucrative, once the cash-flow problem had passed – but there were several things he could do. At the very least, CTR ought to hire more salesmen and beef up production. In addition, it ought to set up a product development lab (a la NCR’s Inventions Department) and get to work on a modernized line of equipment. The plan was expensive but necessary, and Watson recommended that CTR devote the lion’s share of its profit to expansion, not dividends.

But Fairchild turned Watson down. A major stockholder with many friends and associates who, at his recommendation, had exchanged their stock in International Time for shares in CTR, he wanted the firm to issue regular dividends. Since none of Tabulating Machine’s problems were serious enough to merit immediate attention, he believed that it would be wiser to see to the health of CTR’s stock and the company’s financial reputation than to devote its resources to a distant future. Moreover, he believed that CTR’s future lay with International Time, his old company and the firm’s largest division – and if any money was going to be spent on expansion, International Time ought to get it. Although Flint and the CTR board sometimes backed Watson, suspending dividends in 1914 (a year of recession) and 1915, and allowing Watson to set up a small development lab, Watson’s actions were circumscribed by Fairchild and his allies during Watson’s first ten years with the firm.

Watson’s faith in the future of Tabulating Machine was borne out by a look at CTR’s balance sheet. In 1912, the firm’s first full year of operation, CTR earned $541,000 in net profit. Two thirds of that sum came from International Time. (Accounting practices have changed over the years and the figures in this paragraph have been restated in modern terms.) A year later, earnings had risen to $635,000, and once again the bulk of the figure came from International Time. But all of the growth between 1912 and 1913 was derived from Tabulating Machine. Then the economy fell into a slump in 1914 and CTR’s profit tumbled to $490,000. Still, the earnings breakdown proved Watson’s point. International Time and Computing Scale had both lost a considerable amount of business during the recession, but Tabulating Machine continued rolling merrily along, nearly oblivious to the downturn, and its profit had scarcely suffered.

The reason for its success? One quarter of its revenue was brought in by leases, and its customers – generally the accounting departments of large corporations and government agencies were wedded to Hollerith’s equipment. Once clients had installed punch card machines, changing their bookkeeping and administrative practices accordingly, they couldn’t simply remove the equipment and return to the old ways. And since punch card machines tended to improve efficiency and save money in the long run, some customers even tended to lease more of them during bad times. As for the remaining three quarters of Tabulating Machine’s revenues, they came from the sale of punch cards, which customers obviously couldn’t do without and which they were contractually required to buy from CTR. In short, Tabulating Machine possessed an indispensable line of products that produced a steady stream of income in good or bad times.

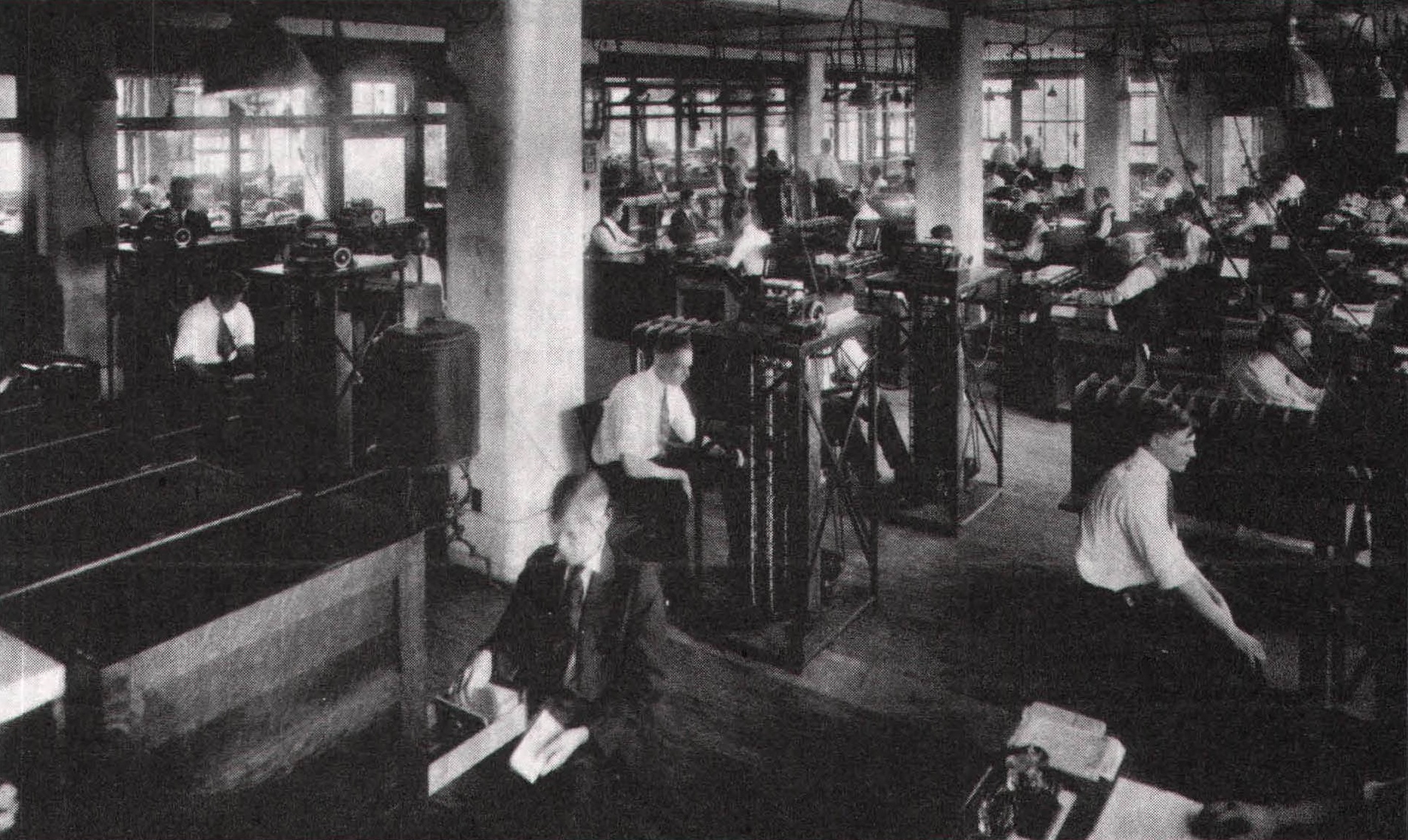

When the economy picked up during World War I, CTR’s overall profit began climbing again. International Time and Computing Scale found new markets for their goods in the various war industries, but Tabulating Machine outperformed both of them. By 1918, it had about 1,400 tabulators and 1,100 sorters on lease in 650 offices in industry and government – a substantial increase over 1914’s rental base – and was turning out more than 110 million cards a month. Led by Tabulating Machine, CTR netted $1.6 million on $8.3 million in sales in 1917 – more than double the sales and triple the profit of 1914. And when, contrary to general expectations, the end of the war didn’t trigger a recession, Watson undertook a major reorganization and expansion program in all three divisions. All this cost a lot of money, and CTR borrowed heavily to pay for it.