By the early 1970s, ICs were sophisticated and inexpensive enough to make a small and inexpensive personal computer possible. Many computer companies, especially Digital and the larger minicomputer makers, could have developed one. Technically, the task wasn’t complicated, either with logic chips or microprocessors. Yet there is a big difference between the ability to make a machine and the realization that a market for it exists. The computer companies couldn’t imagine why anyone – any ordinary person, that is – would want a computer. You don’t need a computer to balance your checkbook or write letters. A calculator is good enough for the former and a typewriter for the latter. And if, for some reason, you did need a computer, you’d be much better off renting a terminal and joining a time-sharing system.

At least two firms dabbled with the idea of making a personal computer in the early 1970s. One of them was the Hewlett Packard Company, of Palo Alto, California, and we’ll return to this lost opportunity later in the chapter. The other was Ken Olsen’s Digital, where an engineer named David Ahl headed a small effort to market minicomputers to schools. In all probability, other companies also toyed with the notion of making a personal, or home, computer. (The terms home computer and personal computer mean more or less the same thing, a small machine designed for an individual’s use.) The arrival of the personal computer was not a triumph of engineering skill but of marketing acumen or – to use a word that does greater justice to the determination of some of the people behind the personal computer industry- vision.

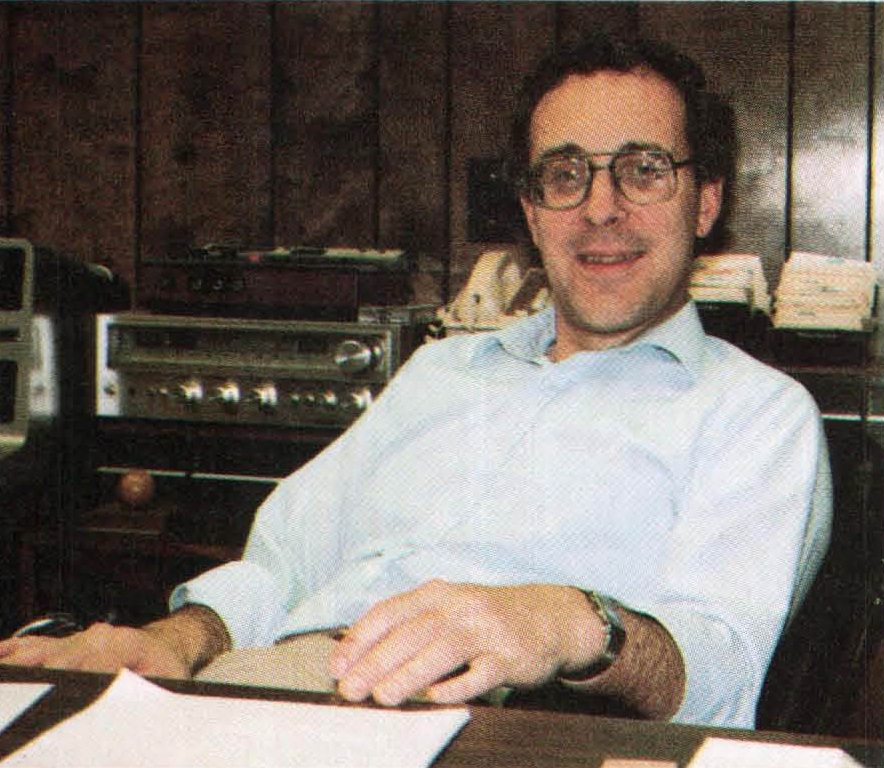

A tall, curly-haired fellow, David Ahl had joined Digital in 1969 as a market researcher. In addition to an engineering degree, Ahl had an M.B.A. and an M.A. in educational psychology. In 1970, he set up an educational products group at Digital, selling packaged computer systems that included both hardware and software to high schools and colleges. Ahl’s little group did quite well; in 1973, it had about $20 million in sales and about half of the educational computer market for minicomputers, with Hewlett- Packard close behind.

Most of Digital’s sales were made to other computer manufacturers or to large institutions, corporate and educational, that had the financial and technical resources to operate their own computers. Very few individuals bought minicomputers, both because they were beyond most people’s budgets and because you had to know a good deal about computers in order to run them. However, every once in a while Ahl’s group received an order from an individual – usually a consulting engineer – for one of its machines. Ahl began wondering whether a market for a simple personal computer existed.

In 1973, Ahl moved to the research and development group, where he helped prepare marketing materials for certain products and investigated new business opportunities. Among other things, the research and development group was working on a small business computer, and Ahl suggested that there just might be a market for the thing in schools and homes. His boss, an energetic engineer named Richard Clayton, was intrigued by the idea. While Ahl explored the marketing side of his suggestion, a small team of engineers developed two prototypes.

One was a computer terminal containing a circuit board filled with logic and memory chips. (In other words, it did not use a microprocessor.) It was a scaled-down PDP-8, a limited version of Digital’s popular minicomputer. (The device resembled the Radio Shack TRS-BO personal computer, developed several years later.) The other prototype was a much more daring effort. It was a portable computer, about the size of a thick attaché case, that contained a monitor, a keyboard, and a floppy disk drive (a small piece of equipment that stores information on a recordlike piece of magnetized Mylar). Floppy disk drives, now a standard part of computers, were new at the time, and the research and development group never managed to get the disk drive on the prototype to work reliably. But the first machine, the one that was made out of a terminal, operated quite well.

In May 1974, Ahl went before Digital’s operations committee, chaired by Olsen, with a marketing plan for the computers. Ahl intended to sell both machines to schools for about $5,000 apiece, not including peripherals, and to anyone else who wanted one. He had contacted the Heath Company, a maker of hobbyist kits, and the firm had expressed interest in offering the computer in the form of a kit. He had even gotten in touch with Abercrombie & Fitch and Hammacher Schlemmer, two well-known retailers of unusual and costly items. Both companies were attracted by the idea of a home computer, but the people Ahl had talked to knew next to nothing about computers and weren’t quite sure what he was getting at. In any event, Ahl asked the operations committee for permission to perfect the prototypes and see if he could dig up some orders.

The committee was split. About half of the members came from the engineering side of the firm; dedicated tinkerers themselves, they had a weakness for interesting new gadgets and were gung-ho about Ahl’s proposal. But the other half of the committee came from the sales department, and they were much more hardnosed. Why would a school buy such a limited machine when a time-sharing minicomputer was much more cost effective? An inexpensive minicomputer could handle many students at the same time; Ahl’s machine could serve only one, and it hardly seemed likely that a school would order a couple dozen of them. Likewise, the salesmen didn’t see a market for the gadget in the home; again, what would you do with it? These were very good questions, and Ahl didn’t have convincing answers. Olsen – a fallible human being, just like the rest of us – ended the debate by coming down on the side of the salesmen, and Ahl’s project was scuttled. Disappointed, Ahl left Digital a few months later. Today, he owns a successful personal computer magazine called Creative Computing.