The seed planted by the Moore School took root all over the United States. Most of the twenty organizations that sent representatives to the Moore School’s course on computers came from companies, universities, and government agencies that had the technical and financial resources to build their own computers – for instance, IBM, General Electric, Bell Labs, MIT, Harvard, the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), and the National Bureau of Standards. The majority of the organizations eventually constructed their own machines, and some of them, such as IBM and General Electric, entered the computer business. By the end of 1947, six computers were under construction in America, three in academia and three in industry.

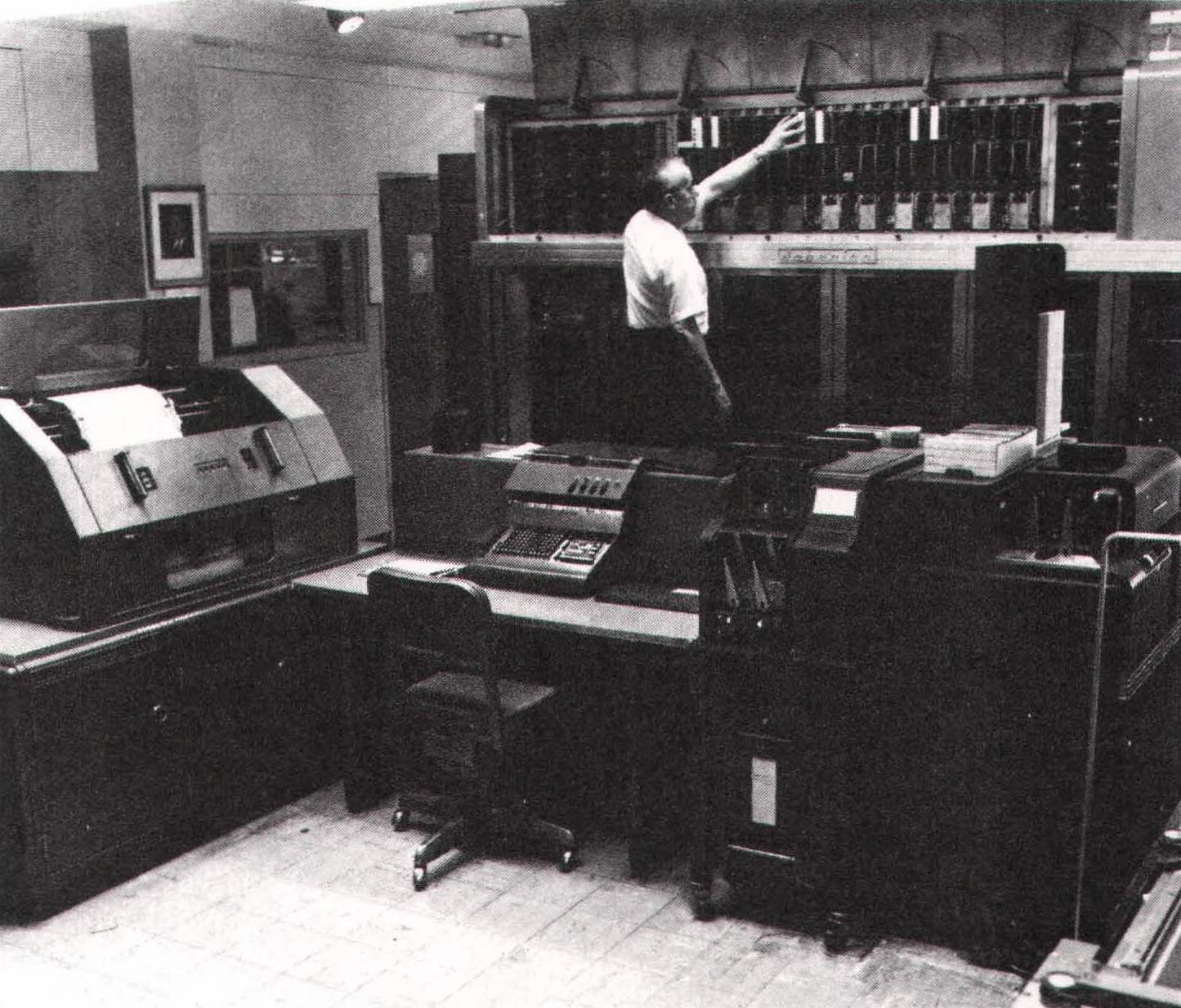

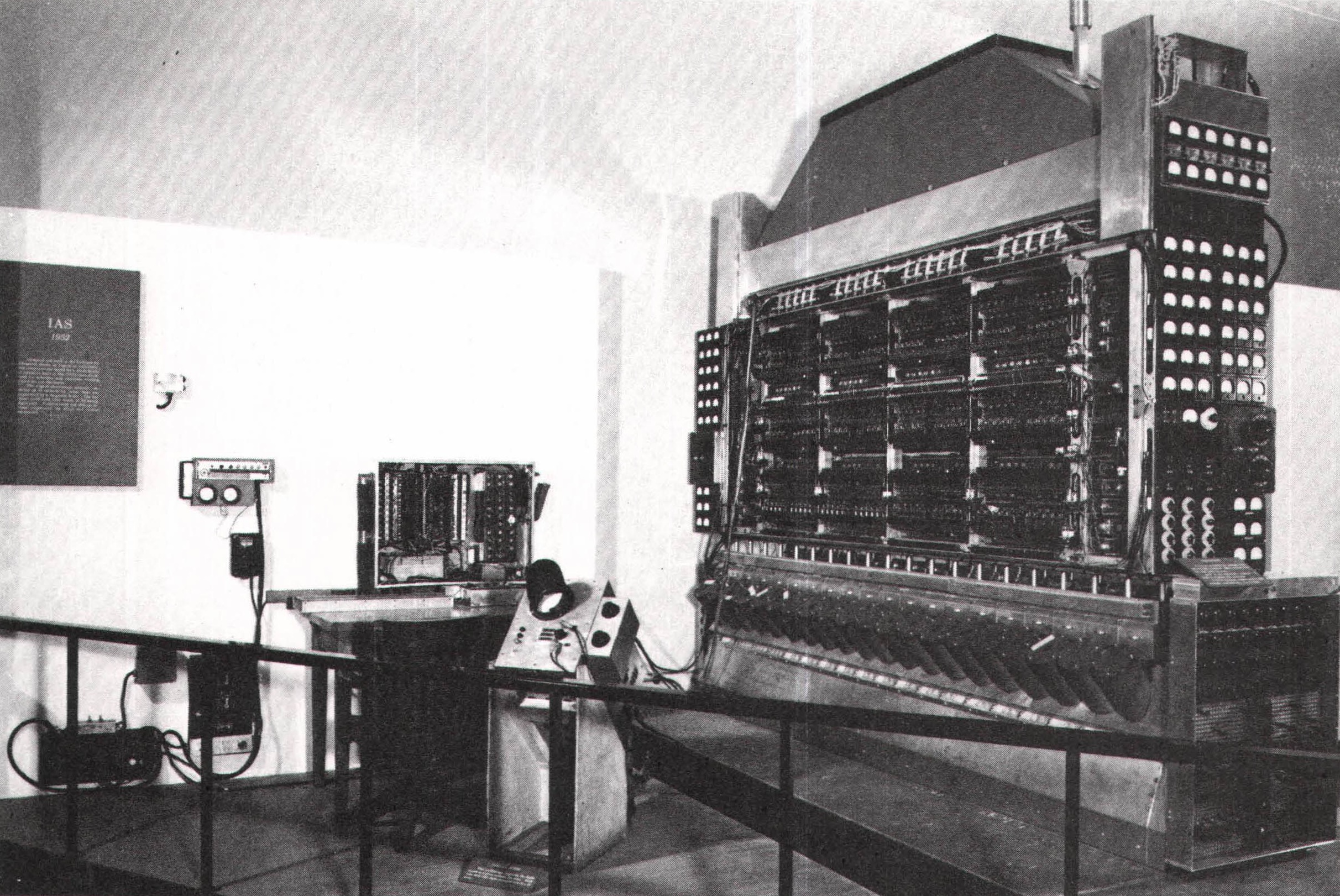

By far the most influential of the academic projects was undertaken by von Neumann at the Institute for Advanced Study. Von Neumann had no trouble rounding up the necessary financing, and the IAS, the government, and the Radio Corporation of America (RCA), which had a new research center in Princeton and wanted to get into the business of making tubes for computers, all chipped in. Meanwhile, other research institutes and universities obtained grants to build copies of the IAS computer, and at least eight duplicates were constructed in the United States and abroad, including the ILLIAC (Illinois Automatic Computer) at the University of Illinois at Urbana; the Johnniac (named for von Neumann) at the Rand Corporation in Santa Monica, California; and the marvelously named MANIAC (Mathematical Analyzer, Numerator, Integrator, and Computer) at Los Alamos.

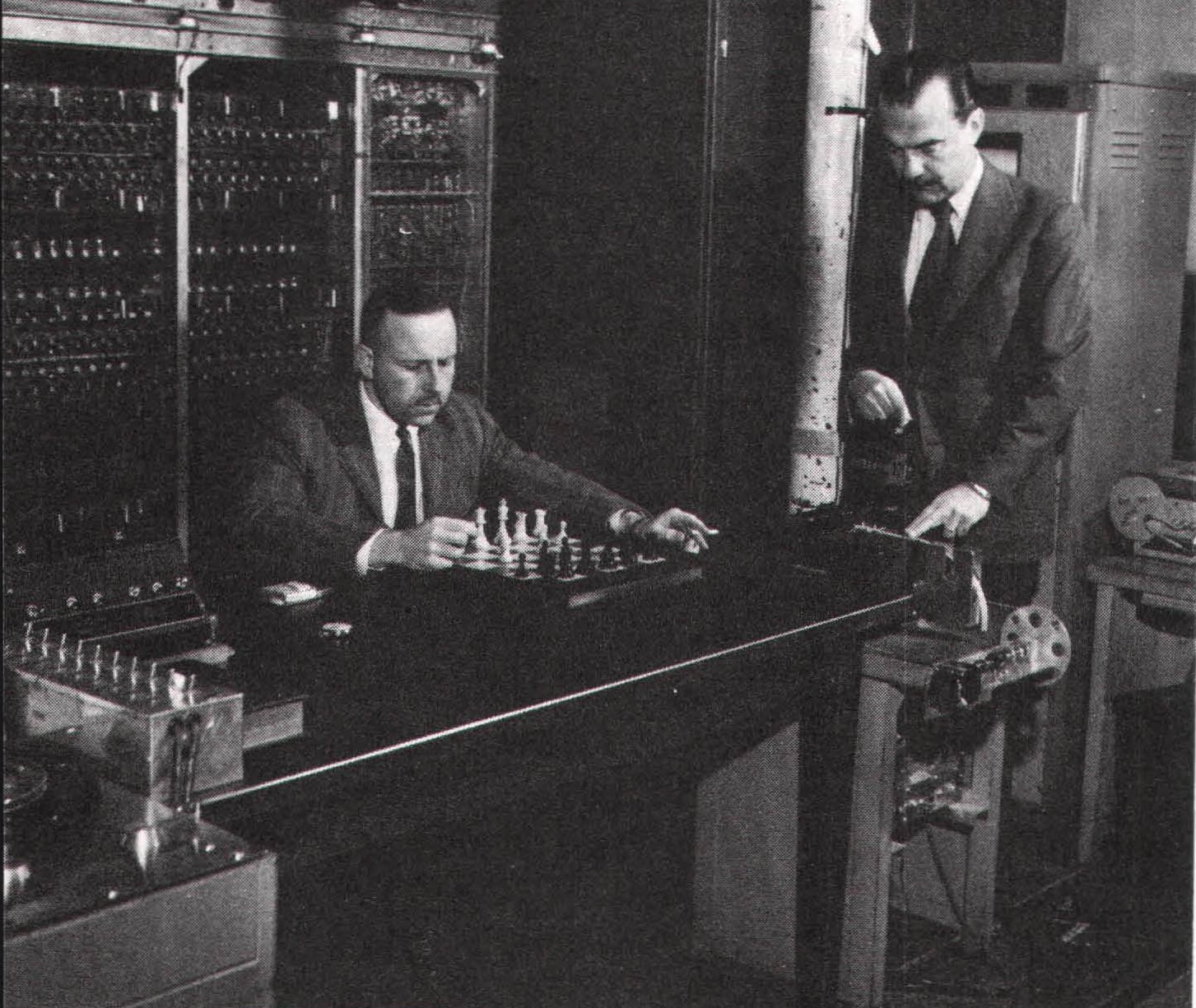

The IAS machine embodied von Neumann’s ideas on computer design, ideas first expounded in “Report on the EDVAC” and refined in another highly influential paper, “Preliminary Discussion of the Logical Design of an Electronic Computing Instrument,” written in 1946 with Goldstine and Arthur Burks, a Moore School mathematician and engineer who had worked on ENIAC and EDVAC. Von Neumann’s ideas on computer design had changed since EDVAC, and the IAS machine was a parallel processor, unlike EDVAC. Although each binary word raced through the machine’s units in sequence, one bit after another, all the bits in each word were stored, and operated on, in parallel, as in ENIAC. Originally, von Neumann had feared that a parallel stored-program computer would be too difficult to build – hence his recommendation for a serial processor in EDVAC – but advances in computer technology had allayed his pessimism. The influence of von Neumann and the wisdom of his approach was such that the IAS machine – a stored-program, parallel processor – became the paradigm of modern computer design, and most computers built since the late 1940s have been “von Neumann” machines.

Obviously, any organization that did a great deal of work with numbers, whether in science, business, or government, could benefit from a computer. In retrospect, the proliferation of computers is easy to explain, although in the late 1940s most people – including many scientists who should have known better – were highly skeptical of the need for such machines. For example, in 1947, Aiken, a stubborn man who was then in the midst of building an electronic calculator without stored-program capability and who missed the technological boat in many other crucial ways, told two officials of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS), which was backing Eckert and Mauchly’s commercial efforts: “There will never be enough problems, enough work for more than one or two of these computers…. You two fellows ought to go back and change your program entirely, stop this… foolishness with Eckert and Mauchly.” Fortunately, the NBS ignored him.