The 1920s was one of the most prosperous periods in American history, and IBM flourished along with the rest of the country. The company’s revenues nearly doubled, from $10.7 million dollars in 1922 to $20.3 million in 1931, while its net profit nearly quintupled, from $1.4 million to $7.4 million. To a large degree, IBM’s success was linked to major economic and demographic changes. Per capita income climbed 42 percent between 1921 and 1929, when the stock market crashed and the country entered the Great Depression, while the gross national product soared an even more spectacular 48 percent. Some industries, such as automobiles and motion pictures, experienced almost exponential growth. At the same time, millions of people moved from the country to the city, hastening the development of a mass-market, white-collar economy that relied increasingly upon data-processing equipment like IBM’s tabulators and sorters.

Another reason for IBM’s success was the absence of effective competition. Throughout the 1920s, IBM had only one real opponent, James Powers, and his company turned out to be a paper tiger, lacking effective managers and salesmen. (During World War I, for instance, when the demand for tabulators and punch cards soared, Powers’ production line broke down repeatedly. CTR happily picked up the slack.) Moreover, as a newcomer to the tabulator and sorter business, Powers lacked IBM’s reputation and financial solidity (solid compared to Powers, anyway). Potential customers considering the jump to punch card machines weren’t inclined to trust their fate to a beginner, and they tended to go with IBM.

But Powers’ position changed in 1927, when he was bought out by the newly organized Remington Rand Corporation. Founded by the industrialist James Rand, Remington Rand was a sensibly diversified and well-financed enterprise with, it seemed at the time, a great future. In addition to tabulators, sorters, punchers, and punch cards, the company made typewriters, adding machines, office furniture, and stationery. From the moment it was born, Remington Rand was the largest business machine company in the country, far ahead of NCR, Burroughs, and IBM, the three biggest firms in the business machine industry (in that order). In its first year of business, Remington Rand’s revenues were three times greater than IBM’s (although its net profit was only slightly higher). Remington Rand seemed to possess the management, resources, and determination to give IBM and the rest of the industry a very hard time. An independent Powers was one thing; a Powers who was part of Remington Rand was another.

As for NCR, Burroughs, and Underwood Elliott Fisher, the fifth largest company in the industry, they also had the means to challenge IBM, but they were quite satisfied with their traditional markets. After Patterson’s death in 1922, NCR fell into the hands of his son, a feckless executive who practically reduced the firm to bankruptcy. As if the ghost of his father were looking over his shoulder, disapproving of every effort to diversify and innovate, Patterson’s heir stuck to registers and nothing but registers. Burroughs also had the skill and resources to compete with IBM, but it, too, seemed mired in the past; a conservative, unimaginative firm, it stayed chiefly with adding machines. Although more aggressive than NCR and Burroughs, Underwood Elliott Fisher wasn’t interested in punch card machines; it was content to remain a first-rate typewriter manufacturer that dabbled in cash registers and calculators.

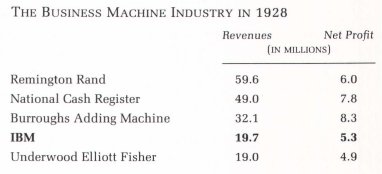

By the end of 1928, then, IBM was the fourth largest company in the business machine industry, with an invaluable line of products and the lion’s share of a very lucrative market:

Ironically, Watson wasn’t much more adventurous than his counterparts at NCR, Burroughs, and Underwood. After all, the world was full of potential punch card customers who had never seen an IBM salesman, and the company had its work cut out for it without branching out into cash registers, calculators, and typewriters. But Watson did make several small acquisitions that complemented IBM’s product line and turned out to be powerful little engines of growth. For example, in 1922, IBM acquired Peirce Accounting Machine and, eleven years later, Electromatic Typewriter, one of the few manufacturers of electric typewriters. Electromatic Typewriter helped IBM develop a typewriterlike electric card puncher that made card punching easier and faster, but the company didn’t flourish under IBM until the late 1940s and early 1950s, when electric typewriters became popular.

IBM weathered the Great Depression with astonishingly little difficulty. Once again, it was the very nature of its business that pulled it through. First, most of its revenues came from equipment leases and card sales. Second, most of its customers – large corporations and government agencies – endured the downturn with relatively little hardship. Third, most of its customers simply couldn’t do without their punch card equipment. So, although earnings and revenues dipped somewhat in 1932 and 1933, they bounced back in 1934 and climbed steadily for the rest of the decade. In fact, IBM was not only immune to the worst of the depression but made an excellent profit out of it. Many New Deal agencies, such as the National Recovery Administration and the Social Security Administration, leased IBM equipment, and the federal government became IBM’s largest customer, with four hundred tabulators and sorters and other IBM equipment on lease.

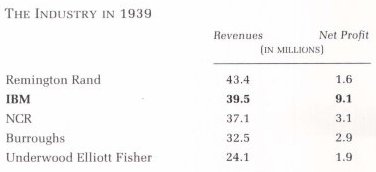

By 1939, IBM was the country’s leading business machine manufacturer. In ten years – spanning the harshest depression in American history – its revenues had more than doubled, while its after-tax earnings had climbed by more than a third. Although Remington Rand’s revenues were still slightly higher, IBM was the healthiest and most profitable firm in the industry, its earnings almost as large as that of the four other leading firms put together:

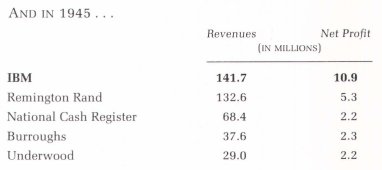

It was World War II that pushed IBM firmly into the lead. In industry, government, and the military, the demand for its data-processing equipment reached unprecedented levels. Not only did the company emerge from the war with significantly higher earnings and revenues than Remington Rand, but years of high profitability had enabled it to accumulate enormous assets – nearly twice as much as the less cleverly and paternalistically managed Remington Rand ($134.1 million to $ 75.4 million). Remington Rand never managed to get more than 20 percent of the market for punch cards and tabulators and sorters. By 1945, IBM possessed the reputation, money, customer base, and managerial skill to enter the computer business and, if it wished, to lead it from the start.