The Difference Engine received a great deal of publicity, and it was only a matter of time before such a machine was built, if not by Babbage then by someone else. In 1834, Pehr Georg Scheutz, a technical editor, printer, and publisher in Stockholm, Sweden, read an account of the project in the Edinburgh Review. Fascinated, he built a small model of an engine out of wood, wire, and pasteboard. Babbage supplied the inspiration but Scheutz came up with his own design; the article in the Edinburgh Review did not contain a detailed description of the engine, and Scheutz, a paragon of self-reliance, did not write Babbage for more information. In 1837, Scheutz’s son, Edvard, an engineer who had been trained in Sweden’s Royal Technological Institute, joined his father’s effort, and the two of them set out to build a full-fledged engine out of metal.

At this point, history repeated itself. Like Babbage, Scheutz and his son soon realized that the venture outstripped their resources and they appealed to the Swedish government for help. But the authorities, who did not wish to go down the same road as the British government, turned them down. The Scheutzes continued the project on their own and, by 1840, managed to produce a small machine that operated to the first order of difference. Two years later, they extended the machine to three orders of difference and, a year later, added a printing mechanism. Once again, father and son applied for government support. This time around, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences endorsed them, and the Swedish Diet advanced 5,000 rix-dollars (about $1,500) on the condition that the inventors finish the project by the end of 1853. Otherwise, the money would have to be returned.

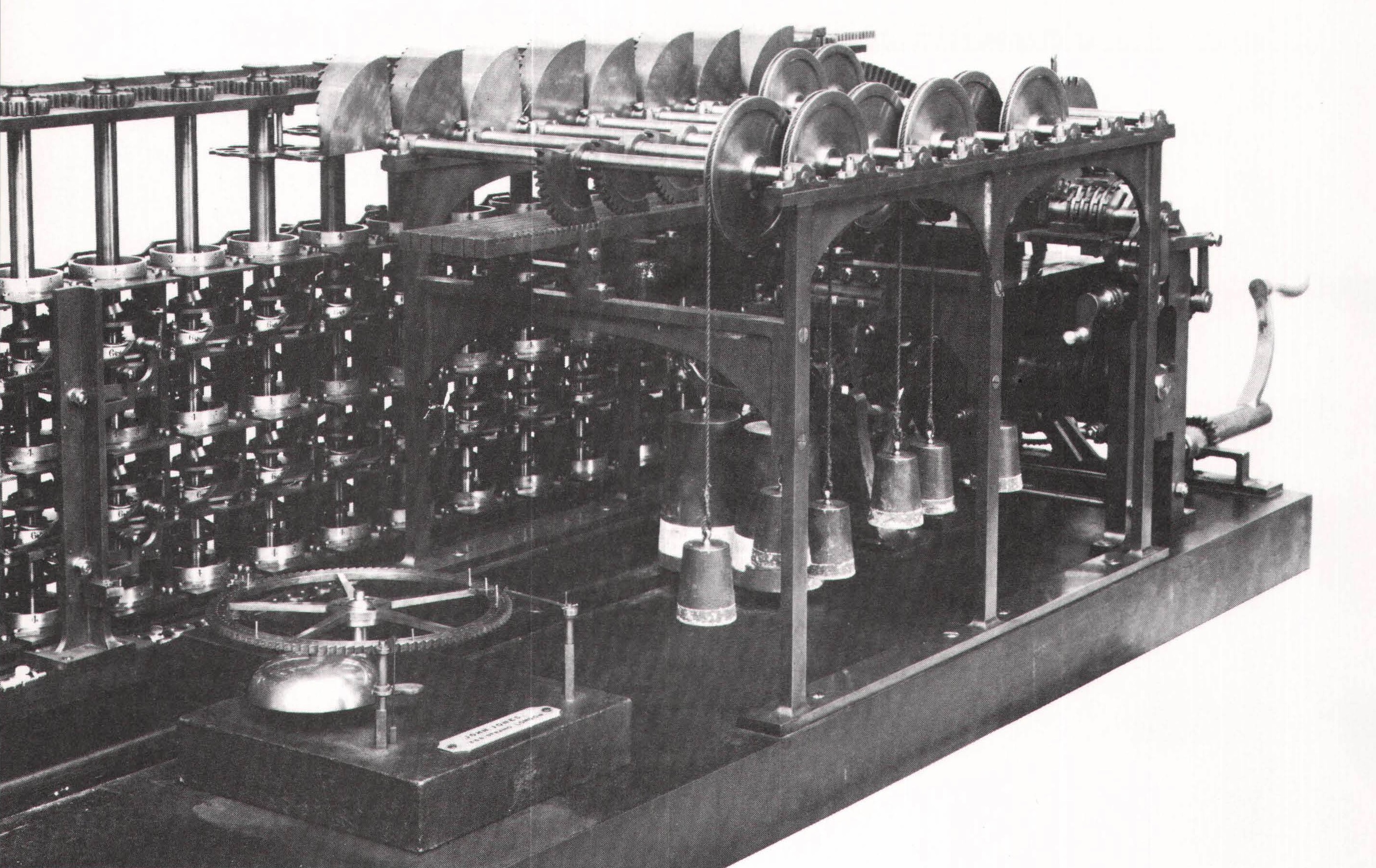

Unlike Babbage, the Scheutzes were an eminently practical pair, and the Tabulating Machine, as they called it, was completed on schedule (though not within the budget). The Swedish engine was not as well built as Babbage’s and, as a result, was prone to error. Nevertheless, it could operate to the fourth order of difference; process fifteen-digit numbers; and print out results, rounded off to eight digits, on molds from which metal printing plates could be cast. In operations involving constant differences, the device could generate more than 120 tabular lines an hour, and was only slightly slower in nonconstant operations, producing, in one test run, about ten thousand logs in eighty hours, including the time spent resetting the wheels for the twenty different equations used in the calculations. No human computer could have worked as fast or as accurately. The Scheutzes’ difference engine was the first concrete demonstration of the enormous mathematical potential of machines.

In 1854, the Scheutzes brought their invention to London, where they demonstrated it before the Royal Society of London. Babbage, ever the gentleman, welcomed his fellow inventors with open arms. The following year, the Swedes entered the machine in the Great Exhibition in Paris and it won a gold medal – thanks, in part, to Babbage, who was a highly respected member of the Institute of France and who had lobbied on their behalf. (Thomas’s oversized Arithmometer, a Baroque throwback compared to the Tabulating Machine, also won a gold medal.) Pehr and Edvard were deeply grateful for Babbage’s support. “Inventors are so seldom found that acknowledge the efforts of others in identical aims,” the father wrote Babbage from Stockholm in 1856,

that your liberality in this respect has, as we hear, made éclat in the French scientific world. Respecting me and son we would not have been so much surprised, having had occasion before, during our stay in London, to learn at your house the true character of an English gentleman; although our admiration of it can only be surpassed by our deep sense of gratitude. We came as strangers; but you did not receive us as such: conforming to reality you received us but as champions for a grand scientific idea. This rare disinterestedness offers so exhilarating an oasis in the deserts of humanity that we wished the whole world should know of it.

The gold medal gave the Scheutzes the recognition they deserved. It also attracted a buyer, which the pair had been searching for almost from the day they had completed the machine. Dr. Benjamin Gould, director of the Dudley Observatory in Albany, New York, acquired the device for $5,000, and shipped it off to America in 1857. There it had a rather odd history. Dr. Gould put Edvard Scheutz (1821-1881) it aside for a year, and finally used it to calculate a set of tables relating to the orbit of Mars. But the observatory’s trustees were unhappy with Dr. Gould’s stewardship – among other things, they considered the purchase of the Scheutz difference engine as ill-advised – and fired him in 1859. After Dr. Gould’s departure, the machine, which required a good deal of mathematical and mechanical skill to operate effectively, was never used again and eventually was donated to the Smithsonian Institution.

Several difference engines were constructed in Sweden, Austria, the United States, and England, where the British Register General, who was in charge of the collection and publication of vital statistics, had a copy of the Scheutzes’ machine built in the late 1850s. The Register General used it to produce a new set of lifetime, annuity, and premium tables for the insurance industry, and it was more heavily used than any other difference engine. All in all, it calculated and printed out more than 600 different tables, including 238 tables for the insurance project. The machine made the Register General’s work somewhat easier, but it required constant attention and often malfunctioned.